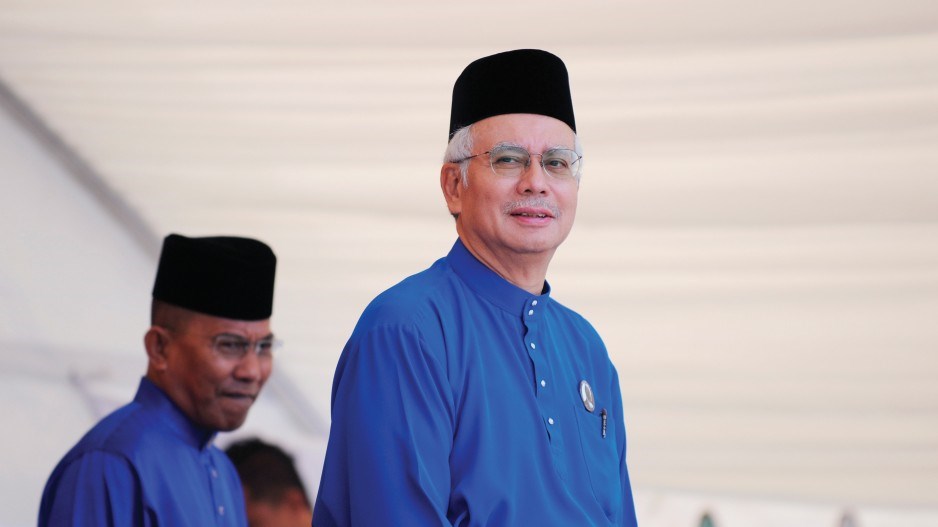

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak has survived more scandals and allegations of corruption than any modern democratically elected leader.

The question troubling many leading Malaysians, however, is how long their country’s reputation as one of the attractive Asian “Tiger economies” can survive Najib’s continued premiership.

On August 9, former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, the father of Malaysia’s rise to economic and business stardom in the 1980s and 1990s, formed a new political party with the aim of ousting Najib in elections due in 2018.

Malaysia’s venerated elder statesman joins an international posse that is on Najib’s trail, including U.S., Singaporean, French and Swiss financial authorities.

At the heart of the suspicions about Najib is the sovereign wealth fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), which he created soon after becoming prime minister in 2009 and which he controls.

Late last month, the U.S. Department of Justice filed civil lawsuits alleging that US$3.5 billion has been misappropriated from 1MDB. The U.S. authorities are seeking to recover more than US$1 billion in assets, including a painting by Vincent Van Gogh and two by Claude Monet. They also want a Manhattan penthouse and a Los Angeles mansion allegedly bought with 1MDB money.

Some of the missing billions appear to have gone to cover Las Vegas gambling debts and – irony of ironies – some went to finance the making of the film The Wolf of Wall Street.

The suit does not name Najib. But it says that someone referred to as “Malaysian Official 1” received over $US700 million illegally from 1MDB. Justice officials have told several U.S. media outlets that the man referred to is Najib.

Najib admits that the money went into his personal account, but says it was a gift from a member of the Saudi Arabian royal family, and that he later repaid most of it. The U.S. Department of Justice disputes this. It says the money came from 1MDB and was first filtered through a Singaporean bank account controlled by a friend of Najib’s stepson.

Allegations about Najib and the $US700 million were first aired by the Wall Street Journal last year. Senior figures in Malaysia’s ruling United Malays National Organisation, including the deputy prime minister and attorney general, attempted to mount a coup against Najib, but instead found themselves purged. Najib got himself a new attorney general, who launched an investigation into the newspaper’s story and announced early this year that nothing untoward had happened.

The allegations by the U.S. Department of Justice and the follow-on investigations in Singapore, France and Switzerland are not so easy to dismiss, however.

The net has now drawn in bankers Goldman Sachs Group Inc. New York State’s Department of Financial Services is looking into Goldman Sachs’ role in three 1MDB bond sales in 2012 and 2013 which raised US$6.5 billion and from which more than US$2.5 billion was misappropriated.

In some ways it is extraordinary that Najib ever became Malaysia’s prime minister. His record was already marked by scandal and worse. French courts are investigating allegations that while Najib was defence minister from 2002 to 2008, the French arms manufacturer DCNS paid $US200 million to an associate of Najib’s to secure a US$2 billion contract to sell Malaysia submarines.

Then, on October 18, 2006, Shaariibuugiin Altantuyaa, the mistress of Najib’s policy adviser Abdul Razak Baginda, was murdered after she demanded US$500,000 to keep quiet about the bribe. She was killed by two of Najib’s bodyguards, who have been found guilty of the killing, but were never asked in court who ordered the murder. •

Jonathan Manthorpe ([email protected]) has been an international affairs columnist for four decades