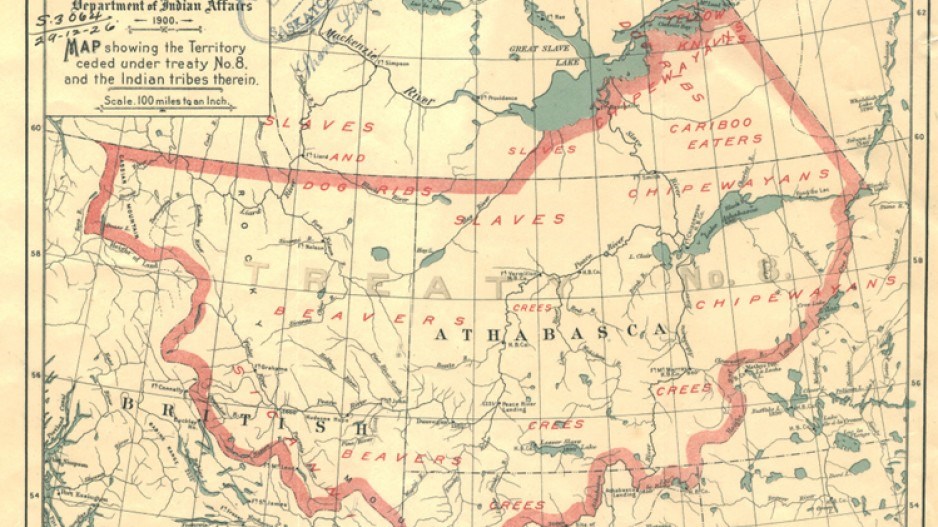

When the ancestors of the Blueberry River First Nation near Fort St. John reluctantly signed Treaty 8 in 1900, they were unequivocal: they would surrender their rights to the land only if they were guaranteed the right to continue to earn a living from it through hunting, fishing and trapping.

Several commissions and Indian agent reports from 1900 onward reaffirmed that unwavering stance.

“It seems clear that Treaty 8 would not have been signed if the Indians had not been assured that their traditional economy and freedom of movement would be guaranteed,” Dennis F.K. Madill wrote in a 1986 analysis of the treaty for Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

But a century of agricultural and industrial development in the Upper Peace region – accelerated in recent years by a natural gas boom – has reached the tipping point, the First Nation claims, and it wants it to stop.

Earlier this month, the 472-member band filed a claim in BC Supreme Court asking for a declaration that – in approving logging, natural gas development, agriculture, road-building and a host of other activities – the B.C. government breached Treaty 8 provisions guaranteeing the signatories’ the right to hunt, fish and trap as they were accustomed to do.

“There’s a huge amount of natural gas development, in terms of wells, pipelines, plants, there’s forestry,” said John Rich, a lawyer representing the First Nation. “There’s Site C – the impact is just huge.”

The case is “novel,” say legal experts, and could have wide-ranging implications for economic development in the Upper Peace region, if successful.

“What they’re claiming could have broad-ranging implications for resource development in their area, and it could be seen as a test case for other First Nations across Canada that have concerns about cumulative effects,” said Stephanie Axmann, a McCarthy Tétrault lawyer specializing in business and aboriginal law.

Most other native-rights court battles in B.C. have involved unceded land. The Blueberry River case is unusual because there’s a historical treaty in place.

“From what I’ve read, with this First Nation, it’s pretty straightforward,” said BC Treaty Commission chief commissioner Sophie Pierre. “Their treaty says they will always have access to their land, and they can’t do that if it’s under water.”

She referred to Site C dam, roughly 50 kilometres southwest of where most Blueberry River members live. Although Site C dam appears to be a trigger, the claim is not based on a specific project or infringement; it cites the cumulative impacts of a century of settlement and industrial and agricultural development.

There is one other case based on cumulative impacts, brought by Alberta’s Beaver Lake Cree Nation (Treaty 6) in 2008. It has yet to go to trial.

The Blueberry River First Nation is not seeking compensation. It wants interim and permanent injunctions stopping any further development that would breach its treaty rights.

“They’re not asking for damages – it would be monumental,” Rich said. “What can be done is protect some areas now. Stop some of this rampant development now, with better planning, so there will be something left.

“Some areas of substance are going to have to be protected, and that’s going to mean some things can’t go ahead.”

One of those “things” could be Site C dam. A successful claim could also have implications for natural gas development in the gas-rich Montney basin.

Treaty 8 states the signatories will have the right “to pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing throughout the tract surrendered … saving and excepting such tracts as may be required or taken up from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes.”

The First Nation will argue that those exceptions have now far exceeded what any of the parties to the treaty might have reasonably expected.

“The question is, legally – if there were proper interpretation of the treaty – just how much can be taken out before the whole bargain is destroyed?” Rich said.

John Rustad, B.C.’s minister of aboriginal relations and reconciliation, said he has visited the region and understands the concern about development.

“We recognize that there is certainly an impact on the land base from economic activity up in that area.”

Rustad added that several agreements have been struck with the Blueberry River First Nation, including an economic benefits agreement from oil and gas activities.

“There was revenue that would flow from the oil and gas revenues that the province received,” he said. “They walked away from that agreement last spring.”

Even if there appears to be a clear breach of treaty rights, Axmann said the threshold for getting an interim injunction to stop all activity is high, because the courts must also weigh the interests of society as a whole.

“I think it’s more likely that it would be a case-by-case basis, rather than a sweeping injunction across all project development in the region.”