Throughout 2015, Business in Vancouver will examine the effects of climate change on the province’s economy. From forestry to tourism to power generation and infrastructure planning, the forecast trend toward higher temperatures will have an impact on many of the industries that have sustained B.C. for decades.

For the first instalment in our climate change series, BIV asked Tom Pedersen of the University of Victoria’s Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions and Deborah Harford of Simon Fraser University’s Adaptation to Climate Change Team to provide a tour of the climate-changed province of the future.

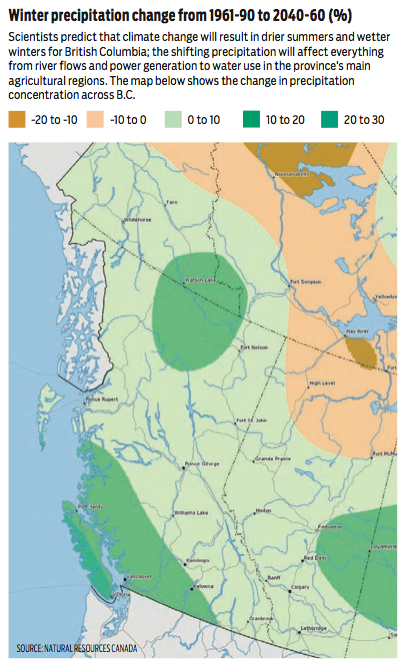

Drier summers and wetter winters. Higher sea levels and lower rivers. Less skiing and more complex and expensive infrastructure planning.

These are some of the changes B.C. residents can expect to see over the next 100 years if global emissions are not cut drastically, said Tom Pedersen, director of the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions at the University of Victoria.

“Right now we’re beyond the worst-case scenario that the scientific community has mapped out in a very sophisticated, formal way,” Pedersen said.

In the United States, the Risky Business Project, a coalition of business leaders and politicians, has begun to highlight the potentially huge economic costs of climate change, from storm damage to crop failure to threats to human health.

In British Columbia, we’ve already witnessed the dramatic effects of climate change. Throughout the 2000s, the mountain pine beetle infestation ravaged the province’s Interior pine forests, leaving distinctive swaths of red-needled, dead trees. Warmer temperatures encouraged the spread of the beetle.

This year’s warm, rainy winter hit ski hills throughout the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island hard; several closed early or didn’t open at all. While next year may be different, the general trend is toward warmer, wetter winters.

“The rate we’re emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere continues to increase,” Pedersen said. “If we’re serious about not allowing climate change to get out of hand, we have to see that rate decreasing.”

Forestry and tourism are just two of the sectors Pedersen expects to be hit hard by the changing climate. Aquaculture and fisheries, agriculture and energy production are also expected to undergo big changes over the next few decades.

Realtors and developers and professions such as engineering and architecture are also increasingly thinking about their responsibility to be knowledgeable about climate change effects, said Deborah Harford, executive director of Simon Fraser University’s Adaptation to Climate Change Team.

“The Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of BC has released a position paper on climate change and what their members should be doing because they are getting concerned about liability,” Harford said.

Under scientists’ “worst-case scenario,” greenhouse gas emissions will have added 8.5 watts of additional heat per square metre to the earth’s surface by 2100.

“That doesn’t sound like much, but that’s a heck of a lot of heat,” Pedersen said. “It will drive [temperatures in] the high latitudes in the northern hemisphere up by probably six or seven degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial time. That’s a huge change.”

The best-case scenario, he said, is the addition of only 2.4 watts. But to do that, “we have to essentially eliminate fossil fuels from our energy-producing diet … by 2050.”

Climate change won’t affect all areas of the province the same way. In the north, the growing season has already gotten longer, meaning farmers in the Peace region may be able to grow some crops more successfully.

But a general pattern of wetter winters and drier summers means that other agricultural areas, like the Okanagan, will have to get a lot smarter about water use.

Lower Mainland farmland will be at risk of flooding or soil salinization, something that Harford said has already happened to some farmland in Delta.

“Once the soil gets salty, there’s nothing you can do,” she said.

River flow in areas such as the Peace and the Kootenays will also change. Wetter winters will mean higher peak flows in the spring, but lower river flow in the summer. That means there will be less water to push through hydroelectric dams on the Peace and Columbia rivers, which together provide 77% of BC Hydro’s capacity.

Glaciers that feed the Columbia River are already in retreat and could shrink to the point that they no longer empty meltwater into the river throughout the spring and summer.

“When you talk about a Site C dam, that dam is going to be designed to last 100 years,” Pedersen said, referring to the new $8.8 billion hydro dam planned for the Peace River.

“How do you build into the design today flow regimes 100 years from now that will protect your electricity production?”

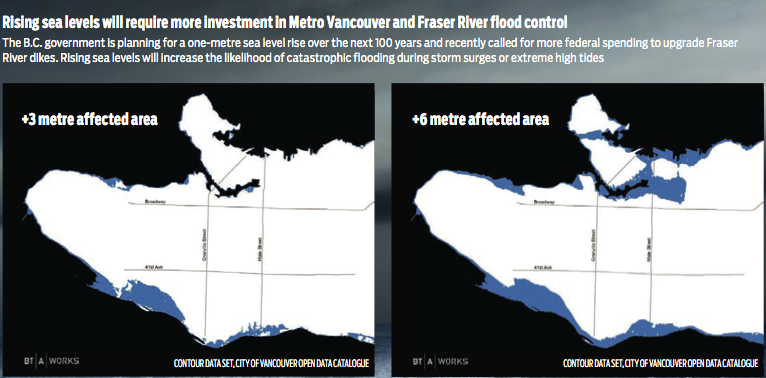

As sea levels rise, the Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley regions will have to invest a lot of resources into flood control and mitigation.

The B.C. government is planning for a one-metre sea level rise over the next 100 years and recently called for more federal spending to upgrade Fraser River dikes.

“We’re also going to have to spend more money – a lot more – on new or revamped infrastructure,” Pedersen said.

But it’s the ocean that could be most drastically altered by climate change. The waters off B.C.’s coasts are particularly affected by ocean acidification, which occurs when ocean carbon dioxide levels rise.

In some pockets of the West Coast, water is so acidic that it has prevented shellfish larvae from forming shells. This has already started to affect shellfish farmers in B.C. and Washington state, but it could also change other parts of the ocean ecosystem.

“One of the principal food sources for salmon – which is a huge economic mainstay for British Columbia – is a little zooplankton that makes their shells out of calcium carbonate,” Pedersen said. “When they start to get negatively impacted by acidification, that has significant implications for the salmon.”

@jenstden