Some farmers and landowners in B.C.’s northern Peace region have found a lucrative side business selling access to water to the oil and gas industry.

The practice is occurring with little regulatory oversight or knowledge of how it could affect the region’s water resources, which are in high demand from unconventional gas producers. That demand is expected to increase with the development of a liquefied natural gas industry.

“It’s been going on for years, [as] long as the industry’s been up here,” said Rick Kantz, vice-president of the BC Grain Producers Association.

Farmers in the area have historically dug pits on their land and let them fill up with spring runoff, groundwater or water from a diverted creek to provide water for livestock.

In recent years, some landowners have built dugouts as large as 150,000 cubic metres (equal to 60 Olympic-sized swimming pools). In applications to the Peace River Regional District and to the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC), the dugouts are sometimes described as being built for both agricultural use and for oil and gas.

But some of the reservoirs are being built solely for the purpose of supplying water to oil and gas companies, Kantz said.

“It’s a good practice. In the long haul it’s going to benefit agriculture. The ability to afford those large reservoirs on your own is just about impractical.”

Kantz added that oil and gas companies typically pay between $3.50 and $5 per cubic metre for water. Depending on where they are located, fracking wells in B.C. use between 10,000 and 70,000 cubic metres per well. The water, mixed with chemicals for the fracking process, must then be disposed of as waste water.

The figures involved suggest landowners could be making tens of thousands – if not hundreds of thousands – of dollars on the sale of water.

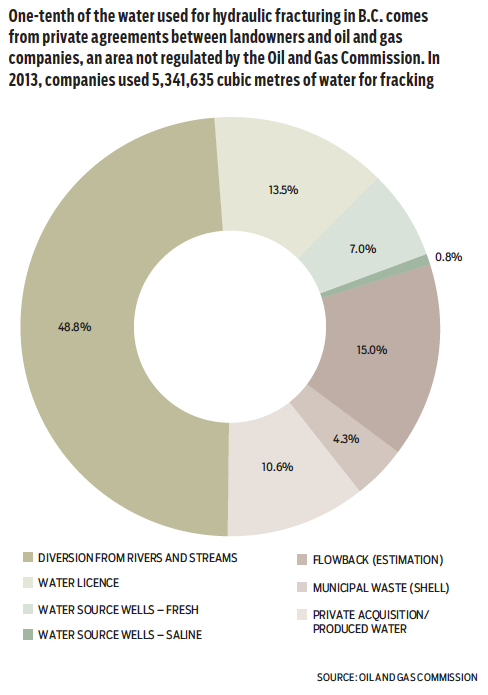

The Oil and Gas Commission is responsible for overseeing water use by the industry, but the commission describes agreements made between private landowners and oil and gas companies as being “outside of regulatory oversight.”

Farmers don’t need a water licence if their dugout captures surface water or groundwater. They do need a licence if they’re diverting water from a stream; if the dugout is being used for non-farm use, the landowner also needs to get authorization from the ALC.

The province owns and manages waterways, but it doesn’t own water that is on the ground but not in a stream. It also doesn’t own the small rivulets created when snow melts in the spring.

Under B.C.’s new water legislation, expected to be in force in 2016, storage of groundwater will require a licence, and all large water users will be required to measure and report the amount of water stored and used.

The ALC approved a 2013 application from the South Peace Hutterian Brethren Church for a dugout for agricultural and oil and gas use, noting: “The Commission’s primary concern is with landowners who do not farm but excavate dugouts wholly for industrial water sales. If this routinely occurs, arable land could be alienated, and surface streams could suffer reduced water flow.”

Brian Underhill, deputy CEO of the ALC, said the commission does not have a policy in place for the practice and has not tracked the number, size or location of reservoirs used by oil and gas.

The Peace River Regional District is concerned about the safety of some of the larger structures. Chris Cvik, chief administrative officer for the district, said some of the larger dugouts might not be properly engineered or inspected.

“You could have a large dugout breach that would release a large amount of water in a short amount of time,” Cvik said.

In an email, the Ministry of Environment said it was drafting regulations for dugout and reservoir construction. BIV was unable to secure an interview with ministry staff by press time.

The district is also concerned about the effect of diverting streams and collecting large amounts of rainwater or runoff.

“Normally that water would go somewhere – into the land or into little creeks that flow into rivers,” Cvik said.

“If you’re removing that water and using it for other purposes, there is an impact.”

The district is involved in a project to measure the amount of water in the region’s aquifers, an initiative that’s expected to take another year to complete.

B.C.’s new Water Sustainability Act needs to be tougher, said MLA Spencer Chandra Herbert, the NDP’s environment critic. For instance, under the new act, groundwater users will for the first time have to pay a fee, proposed at $2.25 per million litres. That price is much too low, Chandra Herbert said.

“The companies in this case seem to have no problem paying more for the water, yet B.C. is gaining not much value from it.” •