That’s the gist of recent criticisms, including damning letters from climate scientists and the government’s own Climate Leadership Team (CLT), on B.C.’s climate change policies and liquefied natural gas (LNG) ambitions, which are being characterized as incompatible.

But has B.C. really become a climate change laggard? Or is it so far out in front that it can afford to pause until the rest of North America catches up?

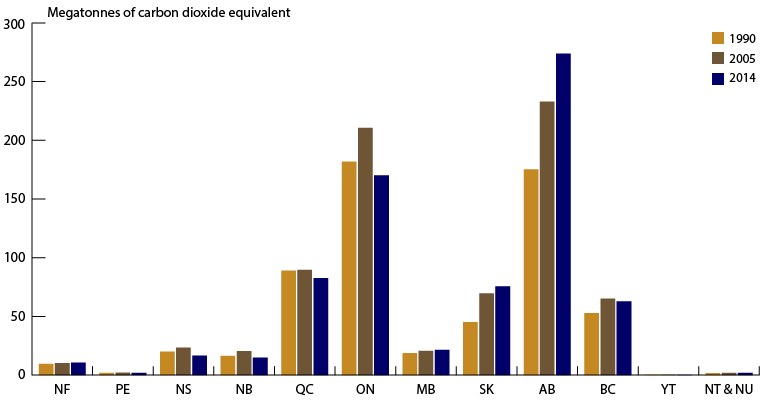

A quick glance at a graph showing current Alberta and B.C. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions illustrates how far Alberta has to go before it can even get close to matching B.C.’s already lean GHG profile.

The one wild card is whether B.C. can swallow an LNG industry and still stick to its carbon diet.

“We are still going to be far and away in front of carbon price,” said B.C. Environment Minister Mary Polak. “We are still the only jurisdiction in North America that is carbon-neutral across our public sector. And that is no small thing.”

Whether B.C. can keep its lead position will depend on two things: its updated climate change plan and a nascent LNG industry.

An update to B.C.’s 2008 climate change action plan is expected sometime this month. Federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna is keen to see it, because it could factor into her decision on whether to approve Petronas’ Pacific NorthWest LNG project in B.C.

Ninety academics recently drafted a letter warning that that single project will make it impossible for B.C. to meet its own GHG reduction targets: 80% below 2007 levels by 2050.

Mark Jaccard, a professor of sustainable energy at Simon Fraser University, was not a signatory to that letter, but he agrees with its assessment.

He says the key to any policy tool – whether it’s a carbon tax or an emissions cap – is that it increases in stringency. But B.C.’s carbon tax has been frozen at $30 per tonne since 2012 and will not start to increase again until 2019.

As a result, the province met its first GHG reduction target in 2012, but will not meet the next one.

However, B.C. already has North America’s highest and broadest carbon pricing.

Had it not frozen the tax at $30 per tonne, B.C. industries and consumers – who already pay some of the highest carbon taxes in the world – might now be paying $60 per tonne, while jurisdictions like Washington state still dither over whether it should implement a US$25 per tonne carbon tax at all.

When the Business Council of BC (BCBC) compared B.C.’s carbon tax with all other jurisdictions, it concluded that the province’s carbon prices are already “among the highest in the world.” (While the price is higher in some European countries, it is applied less broadly than in B.C.)

It has already had negative impacts on B.C.’s cement industry and greenhouses, so the province has hit the pause button to avoid crippling energy-intensive industries like mining, cement plants and pulp and paper mills.

“It would probably contribute to a gradual shrinking of those sectors, if there was not some relief,” said BCBC chief economist Ken Peacock.

B.C.’s starting point on climate change is a public sector that is already carbon-neutral, a low-carbon fuel standard (the only one in Canada), power generation that is already 93% renewable (wind and hydro) and a carbon tax that has been in place since 2008.

Alberta’s starting point is a power-generation system where coal makes up 55% of generating capacity (accounting for 17% of its total GHGs) and natural gas 35%, and a $20 per tonne carbon tax that will go into effect next year and rise to $30 per tonne in 2018.

Alberta plans to phase out coal power and get 30% of its power from renewables by 2030. In other words, 14 years from now, Alberta’s grid will be one-third as renewable as B.C.’s is now.

And it will still have the oilsands, which account for nearly 8% of Canada’s GHG profile, although the Alberta government plans to cap GHG emissions growth at 100 megatonnes annually.

“I understand people want us to continue the actions we’ve taken and continue to lead, but I don’t think it’s accurate to say we have somehow fallen behind Alberta,” Polak said. “It’s great that Alberta and Ontario and Quebec are now coming on board with carbon pricing. None of them, though, have a carbon price that is as broad as ours.”

But what about Petronas’ Pacific NorthWest LNG project? Will B.C. be able to maintain its image as a climate change leader if it develops an LNG industry?

According to the 90 scientists who recently wrote McKenna, the answer is no. Pacific NorthWest LNG alone would add between 18.5% and 22.5% to B.C.’s total GHGs, they warn.

Based on Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency calculations, Pacific NorthWest LNG project alone would produce 11.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually.

“This would make it virtually impossible for B.C. to meet its GHG emission reduction targets and would undermine Canada’s international climate change commitments,” the 90 scientists said in their letter.

But Polak said that assessment was based on the assumption that no further action would be taken on GHG reduction policies specific to LNG, including methane reduction and electrification of gas fields.

Polak said she understands the skepticism when it comes to promoting an LNG industry while trying to keep B.C.’s climate change leader title. But she points out that the Climate Leadership Team assumed an LNG industry would be in place when it set what are believed to be achievable targets.

“The fact is, even the climate leadership team’s report assumed that there would be a liquefied natural gas industry and that there would be plants operating,” Polak said.

B.C.’s goal set in 2008 was a 33% reduction of GHGs below 2007 levels by 2020 and 80% by 2050. The province met its first target (a 6% reduction by 2012) but will not hit the 33% target in 2020.

Because methane has such high global warming potential, reducing it in the upstream production process could have some significant impacts for the natural gas and LNG industry. The CLT has recommended several initiatives to reduce methane.

And because much of the power needed for the gas production, pipelines and liquefaction is typically produced by burning natural gas, extending hydropower to the natural gas fields could also significantly reduce CO2 emissions.

“If you take some of the initiatives that have been recommended around methane reduction and around electrification, you can potentially get the emissions profile for Pacific NorthWest LNG down at about 3.7 [million tonnes],” Polak said.

The Pembina Institute, which is a member of the CLT, says Polak’s numbers are based on only the first phase of what is designed to be a two-phase project.