A historic climate change deal made between the United States and China puts Canada more at risk than ever of failing to adjust to new economic realities, say climate change advocates in British Columbia.

In an agreement announced November 11, Canada’s two largest trading partners committed to cutting carbon emissions by 2030. The U.S. said it would reduce emissions by 26-28% before 2025, while China said its emissions would peak by 2030 and it would aim to get 20% of its energy from clean energy sources by 2030.

The deal comes in advance of climate change talks to be held in Paris in December 2015.

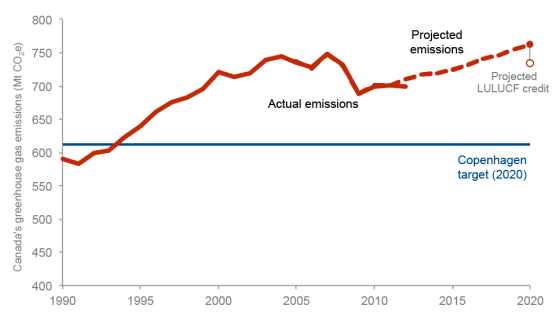

Green Party MLA Andrew Weaver said the announcement is a wake-up call to Canada’s federal government, which has championed petroleum industries, especially the oil sands, as a key driver of the country’s economy. According to emissions projections released by Environment Canada in April 2014, Canada will exceed its own 2020 emissions targets by 122 tonnes.

Canada's historic and projected carbon emissions. Source: Environment Canada, Pembina Institute

“The government said they’re going to have 17% reductions by 2020 … but they’ve taken zero steps to actually make the targets,” Weaver said.

If China and the U.S. back up their commitments with firm policies, there is a risk that Canada could be left scrambling to catch up to a changing economic world where the focus is no longer on fossil fuels, said Matt Horne, B.C. regional director for the Pembina Institute.

“We’ve focused a lot of our energy as a country on trying to expand oil exports, but that demand for oil may not be there if China gets really serious about climate policy,” Horne said.

“Asia will need oil for the future, but if substantive policy follows that agreement they’re not going to need as much oil as we think they need today.”

That shift could also have implications for B.C.’s yet-to-be established liquefied natural gas industry, which is dependent on future demand, especially from Asia.

“You are proposing to build infrastructure that is intended to last 30-50 years,” Horne said. “Based on our research, the global demand [for natural gas] peaks at 2030.”

Weaver said a good first step for Canada would be to introduce a national price on carbon, similar to B.C.’s existing carbon levy. But to effect real change, that price needs to keep rising every year. B.C.’s carbon tax has been frozen at $30 per tonne since 2012.

“It has to cover the whole of the Canadian economy,” Weaver said.

“Companies thinking about their 10-year plan would start to think about the fact that carbon’s going to cost more next year, so maybe they should start to invest now. It pushes people over the hill so they start to change their energy systems from dirty energy to clean.”

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recently issued a dire warning that failure to reduce carbon emissions would result in food shortages, severe weather and social unrest.

@jenstden