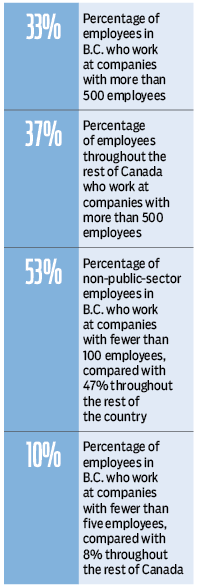

The data shows that B.C. has more workers employed in smaller business and fewer workers employed in larger business than our provincial counterparts across this great nation

In his 1776 The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith saw specialization through the increasing division of labour as the primary path to prosperity.

His now-famous example of a pin factory was used to show how 10 workers, if each were tasked with one specialized job in pin production, could produce 48,000 pins per day.

Without the division of labour and accompanying specialization of tasks, each would be lucky to produce one pin per day. More than a century later, Henry Ford put the pin factory analogy into action with the first modern assembly line, producing the Model T (interestingly a concept that was based on a slaughterhouse line of disassembly rather than assembly, whereby each worker removed a particular piece of meat from a moving carcass).

To this day the notion of specialization remains a fundamental tenet of economic thought and business activity.

But in order to achieve economies of scale, a company must have a minimum number of workers, depending on a range of factors including its industry sector, the size of its target market and its geographic location.

For example, an auto maker will require many thousands of specialized workers to take on the many thousands of specialized tasks required to assemble an automobile. On the flip side, someone running a hot dog stand at the corner of Denman and Davie might require, well, just himself.

Statistics Canada’s Survey of Employment, Payroll and Hours (SEPH) data shows that each province and industry sector in Canada has a unique mix of firm sizes, as seen through published employee counts by establishment size. Excluding industries with a strong public-sector component such as education, health care, utilities and public administration, more than half (53%) of all employees in Canada worked at establishments of 100 or more employees in 2013; the other 47% worked at companies with fewer than 100 workers.

At the two extremes of the company size spectrum, the data shows that 8% of employees worked in truly small business – those with fewer than five employees – while 36% worked for organizations with 500 or more employees.

When considered sector by sector, we see the greatest concentration of workers in smaller companies is in the “other services” category (which includes taxi drivers and barbers), with more than half (51%) of people working for companies with fewer than 20 employees.

This is followed by the forestry sector (48% in establishments with fewer than 20 employees), construction (43%) and real estate and rental and leasing (37%). Conversely, we see the greatest shares of people at companies of 100 or more employees in finance and insurance (80%), mining, quarrying and oil and gas (80%) and transportation and warehousing (67%).

And what about B.C., you ask?

Overall, 53% of non-public-sector employees in B.C. worked at establishments with fewer than 100 employees, which is greater than the 47% seen throughout the rest of the country (that is, Canada excluding B.C.). Furthermore, 10% of employees in B.C. are at establishments with fewer than five employees, versus 8% throughout the rest of Canada. B.C. also has a smaller share of people working at large companies (more than 500 employees): 33% versus 37% elsewhere. In sum, the data shows that B.C. has more workers employed in smaller business and fewer workers employed in larger business than our provincial counterparts across this great nation.

There are a couple of possible explanations for the differences between British Columbia and the rest of Canada: B.C. could have a greater share of employment in sectors that tend to be small, and it could have a greater share of employment in smaller companies within each industry sector when compared with the rest-of-Canada average.

Generally speaking, the broad industry employment structures of B.C. and the rest of Canada are similar, with the largest employment sectors being retail trade (14% of all employees in B.C. and 12% in the rest of Canada) and health care (12% in B.C., 11% in the rest of Canada). That said, the rest of Canada has a greater share of employment in, for example, manufacturing (10% versus 7% in B.C.), a sector that is dominated by larger companies.

Conversely, B.C. has a larger share of employment in accommodation and food services (11% versus 7% across the rest of the country), a sector that is typically made up of smaller companies. In sum, B.C. has a slightly greater share of jobs in sectors that are typically made up of small companies and a lesser share in sectors with larger companies. This is interesting, but it doesn’t tell the whole story.

If we consider each sector in B.C. relative to the same sectors in the rest of Canada, employment in almost all sectors of B.C.’s economy is more concentrated in smaller companies: in 18 out of the 20 sectors published as part of the SEPH data, B.C. has a greater share of employment in companies with fewer than 100 employees than does the rest of the country.

The most pronounced differences are in arts and entertainment (a 34 percentage point difference in the share of employment in establishments of fewer than 20 people in B.C. versus the rest of Canada), forestry (30 percentage points) and manufacturing (13 percentage points).

“So what?” you ask.

The examples of Adam Smith and Henry Ford point to bigger companies being more productive than smaller ones due to their ability to better specialize and thus achieve economies of scale. This is insightful context for a B.C. economy that both includes more smaller companies than its provincial counterparts and needs to boost productivity now and in the future to offset the impacts of an aging and slow-growing labour force.

In a contemporary context, the “bigger is better” hypothesis seems to ring true: just think of how productive one employee of 200 at EA Sports might be, one whose sole task is to render shadows in the latest edition of their NHL franchise. Compare this with an independent website designer who works with only a handful of clients and who does all her own IT work, office administration and marketing, in addition to designing web pages. The potential for better productivity certainly appears to favour EA Sports than the independent web design firm. But just because larger companies have a greater potential for being more productive does not mean that all companies can, or should, become large. Without a mass market for Smith’s pins or Ford’s Model Ts, taking advantage of the economies of scale and productivity gains associated with being bigger are largely irrelevant; furthermore, some companies will always remain small by virtue of what they do or whom they serve.

Productivity gains for these guys are found not through getting bigger, but by doing the things that they do better. •

Ryan Berlin ([email protected]) is the research leader in housing market and economic analysis at Urban Futures.