Growing up in Cologne, West Germany, Peter Englert’s love for science was sparked at an early age. Across the Rhine River, perched atop a hill overlooking the valley was a Bayer chemical and pharmaceutical plant. The logo was always visible from the city, and Englert, who was born in 1949, said it made a big impression on him as a young boy.

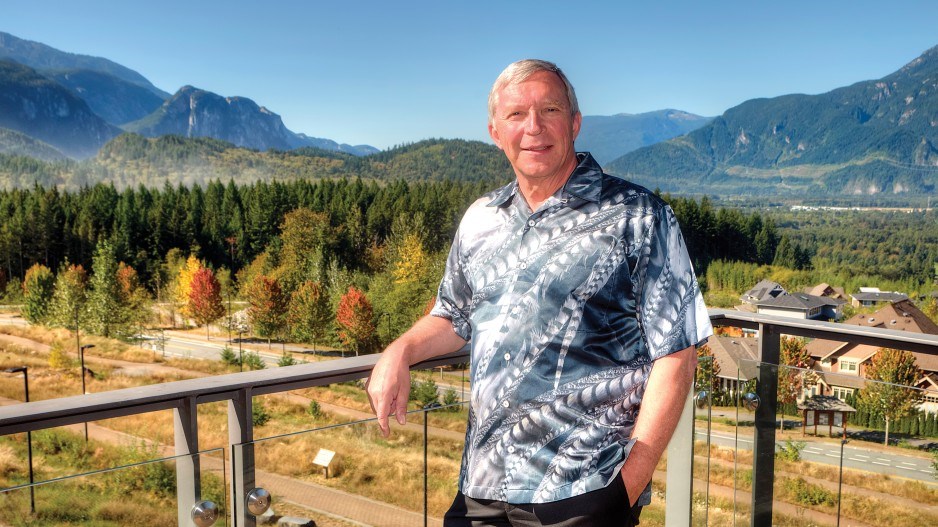

“At that time I always wanted to be a chemist,” said Englert, now the president and vice-chancellor of Squamish’s Quest University. “From my home, I could see this big Bayer company logo which was illuminated into the sky over their major factory. So I thought, ‘Maybe I’d like to work with these guys.’”

After high school Englert headed off to compulsory military service in 1968, and began working in a department of the Bundeswehr (West German federal defence forces) dedicated to researching protection against atomic, biological and chemical weapons.

He took a keen interest in nuclear chemistry and at the same time harboured the ambition of working for Bayer as a patent lawyer, but his studies soon overtook any notion of working in the legal profession. By 1976 he’d obtained his master of science degree in chemistry from the University of Cologne and began teaching at the university while completing his PhD, which he finished in 1979.

He decided to switch things up, or, more accurately, jump continents, in pursuit of learning. Englert asked for a two-year leave of absence to do his post-doctoral work at the University of California, San Diego. He didn’t initially have the travel bug; instead, Englert said, it was more the school’s excellent reputation in the field that lured him to North America.

“That had to do with what I did as a nuclear chemist,” he said. “I was working on very rare isotopes that are produced in meteorites, and I was a specialist in finding and determining them.”

From 1979 to 1981 he was a research fellow within the department of chemistry at the University of California, San Diego. Englert then focused his energy on the field of planetary gamma ray spectroscopy.

“The Mars Odyssey mission was the culminating point of that,” Englert said. “[It] took almost 20 years, from 1980 to 2007. If you get into planetary science or satellites you need to have stamina.”

In 1982, Englert headed back to the University of Cologne, where he was an assistant professor at the Institute for Nuclear Chemistry. However, California came calling again, and in 1986 he took a job as a professor in the department of chemistry at San Jose State University. He also became the director of the university’s Nuclear Science Facility, holding both positions until 1995.

Englert then decided to jump continents again, becoming the division head of nuclear sciences at the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in New Zealand. Looking back on his career, Englert said it wasn’t something he planned, but rather a series of opportunities he couldn’t pass up.

“Nuclear chemistry was funny in that way – it gave me a global career I never thought about. If you would have told me at the beginning I would have said you must be kidding.”

It was in New Zealand that Englert immersed himself in the world of administration, taking on the role of pro-vice-chancellor of research and dean of science, architecture and design at the Victoria University of Wellington from 1998 to 2002.

After that he continued his global journey, serving as the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s chancellor from 2002 to 2005. He returned solely to teaching after 2005 in Hawaii, where he still holds a graduate faculty position. Englert said that while travelling and working abroad continually brought new opportunities, it was an acquired taste at the start.

“I’ve grown to like it,” he said. “It certainly was not in my cards when I started out.”

Englert said getting the chance to work with leading researchers in his field across the world helped make all the travelling enjoyable. He said the experience he gained in New Zealand and Hawaii as a manager transformed him once again, and from there he again leapt continents, becoming chancellor of Quest University in 2015. The private, non-profit school, in which students focus on single “block” courses that run three hours per day, every day, for three and a half weeks, offers a general bachelor of arts and sciences degree. It is the brainchild of former University of British Columbia president and geophysicist David Strangway. Currently living in Kelowna working on a non-fiction book about Angola, where he grew up as the son of missionaries, Strangway said Englert has shown both the competence and resilience it takes to lead a university, especially one like Quest that has such an experimental spirit.

“I find him very sympathetic to people’s issues and students’ issues; at the same time he has a very tough role to play in making decisions,” Strangway said. “Obviously everybody doesn’t like certain decisions you make as a president, but, guess what, I’ve been through that myself and I know all about it.”

Englert said he fielded job offers while in Hawaii, but it wasn’t until Quest came along that he decided to jump, again.

“I didn’t say immediately that I wanted to go for it; it took me a moment. I started to read up, and I started to understand Quest University and then it became something where I was like, ‘Well, this is really interesting, I really would like to do this.’”

Looking back on what could be seen as parallel careers in science and university leadership, Englert said there are similarities between the two.

“If you have an open mind you can translate your reasoning, your quantitative thinking into evidence-based action,” he said. “And that’s where the connection comes [that links] a scientific mind and an administrative management mind.”

He did note one thing the sometimes insular world of science doesn’t teach: the all-important human component to higher education.

“That’s what science doesn’t prepare you for, working with people, getting the best ideas out of people. And I’ve found over the years that I’ve always liked to work with other people.”