In 1977, Jim Iker drove his Volkswagen van from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Topley, B.C., three hours north of Prince George.

The 25-year-old Iker had grown up in the suburban Ontario towns of Welland and Oakville. Now he was headed to a tiny village of just 150 people located in the rugged terrain of northern British Columbia.

It was the start of a lifelong career in teaching – and activism.

"I got involved in Burns Lake Teachers' Union right away," Iker said.

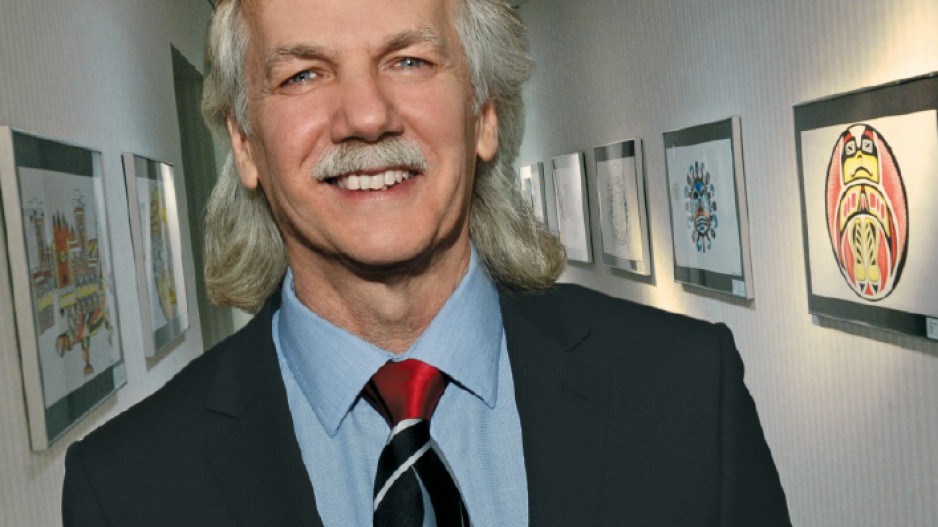

After six years of sitting on the executive committee of the British Columbia Teachers' Federation (BCTF), the union that represents the province's 41,000 public school teachers, Iker became president of the BCTF in 2013.

He follows outgoing president Susan Lambert, a fiery and outspoken leader who presided over a particularly contentious bout of bargaining. Her time as president included a year long labour action that saw teachers refusing to fill out report cards, culminating in a three-day strike in March 2012.

The BCTF also wrestled with the government over how to interpret a 2011 court decision, which ruled that a 2002 law that removed the union's right to negotiate class size and composition was unconstitutional.

The Ministry of Education and the BCTF are continuing to negotiate a new collective agreement for teachers. The parties have been in talks since the last agreement ended in June 2011. The relationship between the union and government has been rocky for over a decade: since the Liberals came into power in 2001, teachers have been legislated back to work three times.

In contrast to Lambert, Iker is a quieter presence, a man who has spent more than 30 years teaching small children in a rural community most Vancouverites would have a hard time finding on a map.

He describes himself as a calm person and a good listener.

"I'm firm when I need to be firm, and I also know when you need to compromise."

Jacquie Griffiths, the former chief negotiator with the BC Public School Employers Association (BCSPEA), says that combination of kindness and passion makes it "tough to be mad at him."

"He's a very passionate union leader, and I would say he has compassion for the members he represents," Griffiths said. "You see that when you're bargaining with him, but he's also quiet and gentle in his approach."

For Iker, the issues of more funding for public education and smaller class sizes are rooted in the social justice causes he first became involved with in high school.

"I've always believed that there needs to be a better world, that we need to close the gap," he said. "We come from a rich society, and seeing people in poverty, people suffering, I always had a concern that we should be able to make things better for everybody and share the wealth."

As a teenager, Iker got involved in his first cause, a protest of California fruit and vegetable growers in support of farm workers who were trying to form a union. He also volunteered at a local community centre, working with children from his working-class neighbourhood.

He always knew he would be either a social worker or a teacher. After completing a sociology degree at McMaster University, he travelled around Canada with his first wife, then completed his teaching certificate at Dalhousie University. He applied for jobs in the Maritimes and in B.C.

"I got a phone call from Topley elementary," he recalled. "They were looking for a male primary teacher. I had no idea where it was."

A year after arriving in Topley, Iker's marriage ended, and he became a single father. In Topley, he found a strong community that helped him raise his son. He lives there still with his second wife, also a teacher, on a 50-acre property "that we don't do anything with. No animals, other than a cat."

He makes a point of noting that Topley elementary is now gone, one of more than 200 schools in B.C. that have closed since 2002.

For the past seven years, Iker has shuttled between Vancouver and Topley. He gets home for three or four days each month.

"It's so good for me to be able to go back," he said. "I tell people that going home to the north grounds me."

On the tough bargaining ahead, Iker said he is optimistic that a resolution this year is possible. Class size and increased pay for teachers remain key issues, but it all comes with a price tag: like BCTF leaders before him, Iker is adamant there needs to be an increase in funding for public education.

He said B.C. currently falls behind other provinces on teacher pay and on per-student spending.

"Statistics Canada has reported that we fund to the tune of $1,000 less per student than the Canadian average," he said.

"B.C. is not a have-not province, and there's no excuse that we're at the bottom."

He believes cuts to education have directly affected B.C.'s child poverty rate, calculated this year as the highest in Canada by First Call: BC Child and Youth Advocacy Commission.

"We've got a flatlined budget for the next three years that won't even cover inflation. I'm hoping we can advocate and develop a plan for stable funding that at least brings us up to the Canadian average."

Last June, Education Minister Peter Fassbender replaced the BCPSEA's chief negotiator, Griffiths, with a government negotiator, Peter Cameron. While Iker said the move was disruptive and confusing – it followed five months of what he described as productive negotiations – he said talks are continuing with both Cameron and Fassbender.

Iker said his decades of experience as a teacher and a union leader have given him perspective: for instance, he has already met Cameron, at the bargaining table in the mid-1990s, when Cameron was a negotiator for the NDP government.

It also helps to keep him focused on the end goal.

"I taught pre-union, pre-collective bargaining," he said. "I've taught anywhere from 11 to 39 kids in straight or split classes, and then when we unionized we had negotiated class size limits.

"So I've seen the impact of having negotiated working conditions in the collective agreement."