In a glass display case in the foyer of the Burnaby headquarters of Ballard Power Systems (TSX:BLD) is a photo of Ford's first hydrogen fuel cell-powered car.

It was taken in 1999, when Ballard was predicting hydrogen powered cars would be in showrooms within five to eight years, and capital market ebullience for clean energy was driving Ballard stock toward a dizzying peak of $192 per share.

But by the start of 2006, as investors wearied of hydrogen hype, Ballard's share prices had dropped to around $5 per share, the company had an annual cash burn of $80 million and still had no market for its fuel cells.

Despite the fact it now has customers and sales and is on the cusp of breaking even, investors continue to vote with their feet. Ballard's shares now edge down toward the $1 mark, to the great frustration of the company's shareholders.

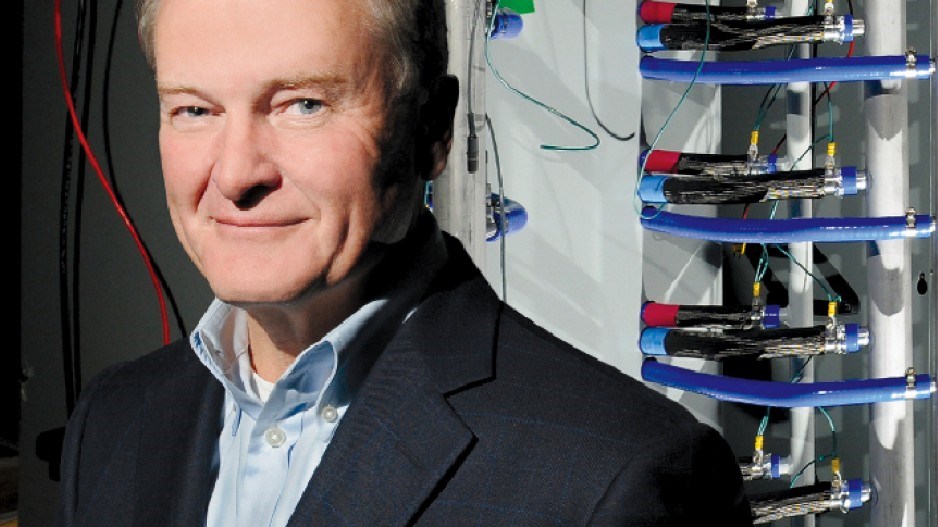

"We wear the same frustration because we are shareholders too," said John Sheridan, the 57-year-old former Bell Canada (TSX:BCE) executive who was brought on board six years ago turn the company around.

"Did I think at the time we were going to make faster progress? I sure did. But when you look back and you think of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and if you look at how North America shifted away from support for clean energy, I don't think it's surprising there's some real headwinds out there."

Those headwinds include some well-earned skepticism from institutional investors. Since it was founded in 1987, Ballard has been more successful at selling an idea – a zero-emission energy source – than actual products.

But even one of the company's harshest critics – technology analyst Brian Piccioni – acknowledges Ballard is a very different company, thanks to Sheridan.

"I think he's done extremely well," said Piccioni, who expressed grave doubts about the company's prospects when he was an analyst for BMO Capital Markets. "People will say, 'What the hell? The stock has gone down by 90% under his tenure.' What people don't realize is that you've got to play the hand you're dealt."

Piccioni points to Sheridan's blue-chip resumé for shareholders looking for assurance that he can do what none of his predecessors have done: turn a profit.

"What I always found amazing is, if you look at the guy's history, you don't usually get people of this firepower running companies like Ballard," Piccioni said.

That history includes more than two decades with Bell in senior executive roles. Sheridan earned a BA degree in environmental studies from the University of Waterloo, a BA from Wilfred Laurier University's School of Business and a master's degree in economics from Queen's University.

Starting off as senior engineering associate with Bell, Sheridan eventually moved up to president and COO, leading a staff of 50,000.

In 1992, he left Bell and he and his wife and two sons moved to England, where Sheridan founded Encom, a British telecom and cable TV company. In 1996, after selling the company, he returned to Canada and went back to work for Bell.

Sheridan retired from Bell in 2003 and was looking for a new challenge when he was invited to chair Ballard's board of directors in 2004. In 2005, he stepped in as interim CEO, with the departure of his predecessor Dennis Campbell, and in February 2006 agreed to take on the role full-time and oversee a major restructuring.

"It was at a total crossroads," Sheridan said. "If you go back to 2005, Ballard had no products, no customers, no path to profitability. Ballard was an R&D company."

He agreed to take the job, he said, because, for one, he likes a challenge. For another, he believes hydrogen holds great potential as a clean power source. He also admits Vancouver's lifestyle helps keep him here. He plays golf and enjoys hiking, cycling and walking his Bernese mountain dog.

"If you think of those things, where is a better place to live in the world?"

In 2007, Ballard divested itself of its automotive fuel cell division to Daimler and Ford to focus on areas with better short-term commercial prospects, and shed more than 240 positions in the process. More than 100 Ballard employees stayed in Ballard's Burnaby headquarters but moved over to the Daimler-Ford Automotive Fuel Cell Cooperative.

Ballard focused on four business entities that, while not as sexy as hydrogen car technology, has more potential for shorter-term commercialization: backup power for telecoms, fuel cells for forklifts and buses and industrial-scale power generation (distributed power).

Sheridan said there is a good market for backup power systems for telecoms in places like India, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, where power grids are unreliable.

One challenge for these systems is having a local source of hydrogen, which is typically made from natural gas. Ballard solved the problem at the end of July with the $7.7 million acquisition of a reforming technology made by IdaTech that produces hydrogen from water and methanol. Ballard can now market backup power systems with built-in hydrogen fuel making capabilities.

Earlier this year, Ballard said it expected 2012 would be the year it broke even on $100 million in revenue. But a delay in an order for fuel cell stacks for buses in Brazil forced the company to adjust its guidance in June; it now expects to end the year with a $5 million loss.

"We still think there's a great market in Brazil for fuel cell buses, but we're no longer counting on it for this year," Sheridan said. "Long story made short, it's taking us a lot longer than we thought."

Sheridan acknowledges the investor fatigue that results from yet another missed target.

"Is our share price undervalued today? We think it is, but we've got to prove that. We've got to generate earnings and grow. If we do that successfully, we'll be rewarded in the equity markets. If we don't, we'll be an historical footnote along the way." •