Vancouver's civic religion may well be environmentalism, as U.S. urban planner Andrés Duany noted during a visit to the city in 2005 – and the proliferation of community gardens and hipster horticulture is among the latest manifestations of civic piety.

According to the city, there are now 85 gardens operating under the aegis of the city, schools, churches and other organizations. That works out to a total of 3,700 plots.

An additional 17 farming businesses operate in the city, working 8.2 acres of land – up from the approximately seven that worked just 2.3 acres in 2010.

The largest by far is SOLE Food, which attracted attention this year when it set up a two-acre tract of planters on the parking lot adjacent to BC Place stadium at Pacific Boulevard and Carrall Street. It's a step up from the initial site at Hawkes and Hastings and the other three sites (4.5 acres in all) SOLE Food operates around the city.

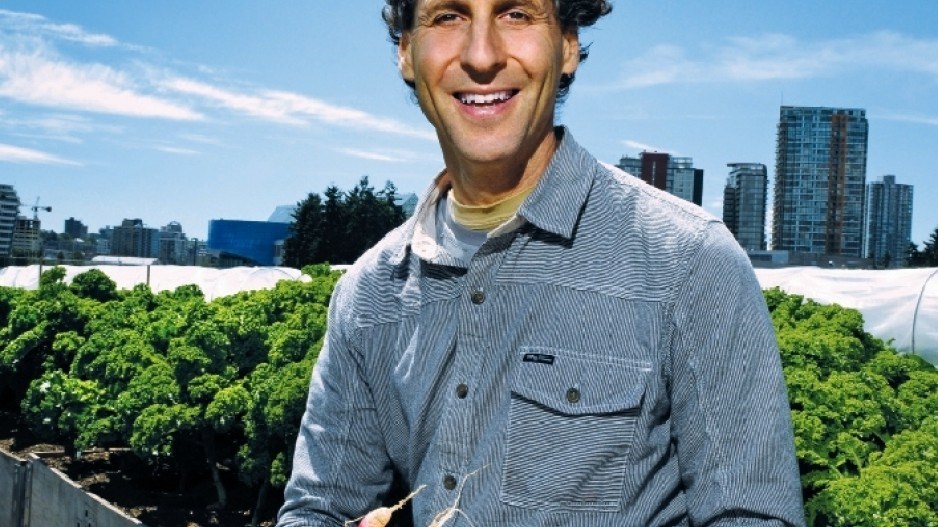

"Nobody does this, not on this scale," said Michael Ableman, whose business card styles him chief executive agrarian of SOLE Food.

The seed for SOLE Food was planted in 2009 when Seann Dory, sustainability manager at Downtown Eastside employment organization United We Can, approached Ableman – well known for his efforts promoting community-oriented agriculture in California and the Gulf Islands – for help launching an urban farm.

Spun off from United We Can in March 2011 through Cultivate Canada Society, an independent registered charity, SOLE Food sought and received funding for expansion from the Radcliffe Foundation and Vancity, which provided $250,000 in support.

SOLE Food now employs 25 people, many from the Downtown Eastside, and supplies seasonal produce to a half-dozen farmers markets during the summer, as well as close to 30 restaurants and approximately 40 households throughout the year.

"Our primary goal is to provide meaningful employment to people who in some cases don't have access to any employment," Ableman said. "The second goal is really to provide a credible model of urban agricultural production. Because most of what people refer to as urban agriculture is often urban horticulture."

The venture has won several awards for its transformation of vacant, often contaminated sites, into farm sites. Most recently, the Real Estate Foundation of BC recognized SOLE Food for its work as an innovative non-profit in sustainable land use as part of its Land Awards.

Ableman, however, sees SOLE Food as more than either an employment program or a way to put vacant lots to good use.

"We're not going to the market and saying 'Buy this because it's supporting the Downtown East side.' We will not do the poverty porn thing," he said. "The product has to be good, first. And then if people want to know the story, fantastic. But buy it because it's good, first and foremost."

The story is about how the food was grown, and it goes well beyond whether or not the food is organic.

"I'm interested in going beyond organic as a conversation," he said. "People get hung up on that, and we need to go beyond that and ask some bigger questions: about labour, about food miles and energy; about soil health."

Vancouver chef David Hawks worth first bought food from Ableman when he was at West on Granville Street. Next year, he hopes to source an exclusive mix of vegetables from SOLE Food for his eponymous restaurant Hawksworth at the Rosewood Hotel Georgia. While many farms now offer local produce, he finds Ableman's marriage of local food production with a community vision compelling.

"I'd rather support something that's smaller, and they're really changing the lives of some people I see on a daily basis," Hawksworth said. "And the stuff is not cookie cutter – [they're] quite fun vegetables. It's not just cherry tomatoes and bell peppers."

Now 58, Ableman first encountered farming on a commercial scale at 18 when he joined an agricultural commune in Ojai, California. His grandparents were farmers in southern Delaware, and his father was a broad caster-turned-lawyer who always had a vegetable garden. But in 1972, with war in Vietnam still making headlines and the 1973 energy crisis just around the corner, Ableman saw farming as an opportunity to make the world a better place.

"There [are] a lot of things I could have done that were part of the problem. I wanted to be part of the solution," he said. "I got to learn this whole range of agricultural skills. After that experience I had the fire lit."

The commune farmed 4,000 acres, processed what it grew and ran natural food stores. But the people buying its products were primarily well-to-do consumers who could afford what was then a niche category. Ableman saw the potential to bring organic food to the masses, not just consumers but also communities.

"I felt for some time that there must be another way to expand this movement, so that not only could the food reach other less-privileged communities, but so we could teach other people how to do this," he said.

Moving to Goleta, California, in 1981, he became farm manager at Fairview Gardens. An opportunity to buy the farm led to Ableman establishing the Center for Urban Agriculture in 1997 to operate the farm as a not-for-profit. He would oversee the venture until 2006.

"This was a way in low-income communities, which were primarily urban, that we could do this. We could provide jobs and food, so that was my version of what I saw [as] urban agriculture."

Along the way, he met the likes of David Brouwer, founder of Friends of the Earth, and writer Wendell Berry, a friend he describes as "a great thinker in the New Agrarian movement," who was championing farmers markets and community-based farming well before J.B. MacKinnon and Alisa Smith captured the popular imagination with The 100-Mile Diet.

"[He's] had quite an influence on my thinking," Ableman said.

But in running the centre, Ableman found himself more administrator than farmer and yearned to return to his roots. During his 20s he had helped a friend build an A-frame near Nelson and also tended sheep on a ranch near Vavenby, north of Kamloops. Returning to B.C. for a cycling tour of the Gulf Islands with his wife Jeanne-Marie in 2000, he saw an alternative to California and the family moved north in 2001.

He now lives on Foxglove Farm, a 120-acre property on Saltspring Island, where he farms and operates the Centre for Arts, Ecology & Agriculture. The new centre explores "the vital connections between farming, land stewardship, food, the arts and community well being," in regular retreats, classes and camps and other events.

The centre also concentrates on modelling economic possibilities for small-scale agricultural operations, something Ableman will test as SOLE Food plans a retail outlet for a new farm site planned for Main and Terminal in 2013. Small-scale food processing is also possible, but he conceded: "We're not there yet."

Indeed, if there's one thing Ableman's noticed from a lifetime in community farming, it's that greater awareness hasn't necessarily led to greater participation in the dirty work of food production.

"You can do an apprenticeship at a million different places; there's a lot of opportunity," he said. "But the thing that hasn't changed is that there still aren't that many more people doing the work. There's a lot of people talking about it. There's lots of books and articles and movies, but still very few people whose hands are actually in the ground doing the farming."