Just three and a half months after Petronas and its partners pulled the plug on a $36 billion liquefied natural gas project in B.C., one of the partners has reappeared in Alaska.

And what Sinopec has planned for Alaska could blow B.C.’s LNG ambitions right out of the water, if it ever gets a final investment decision, according one industry analyst, because it could sew up the market in China for LNG that B.C. projects were hoping to capture.

On Wednesday, November 8, Alaska Gasline Development Corp. – a state-owned entity – announced a joint development agreement that would see Chinese companies and banks partnering in a US$43 billion LNG project in Alaska. The announcement coincided with U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to China.

The Chinese partners include China Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec), which held a 15% stake in the now-dead Petronas-led Pacific NorthWest LNG project.

The financing partners include the China Investment Corp. – a sovereign wealth fund with US$800 billion in deployed investments – and the Bank of China.

“As the most internationalized bank in China, Bank of China is willing to facilitate the China-U.S. energy cooperation and provide financial solutions for this transaction by taking advantage of its vast experiences and expertise in international mega-project financing,” the Bank of China said in a joint press release.

The project also has the backing of the Alaskan government, which would have a 25% stake in the project through the government owned Alaska Gasline Development Corp.

“They’ve taken an equity stake,” said Jihad Traya, manager of natural gas consulting for Solomon Associates. “It takes away all that agency issue and all that other discussion around LNG taxes and fiscal certainty. You’ve now created fiscal certainty.”

So not only does the project have the financial backing of one of the world’s biggest banks, and a government equity partner, it also has all of the advantages B.C. boasted.

LNG advocates, including the Shell-led LNG Canada, have touted the so-called “B.C. advantage” when it comes to developing an LNG industry here, compared with American competitors on the Gulf Coast.

Those advantages include an ocean of gas in northeast B.C., short shipping distances to Asia, and a cold climate, which reduces the energy input costs for chilling natural gas to minus 160 Celsius. Alaska has those same advantages.

The B.C. advantage does not appear to be sufficient to keep major energy players interested in B.C. Asian energy companies, including Chinese companies, have been voting with their feet.

In mid-September, just two months after Petronas announced it was pulling the plug on its Pacific NorthWest LNG project in Prince Rupert, Nexen, owned by China’s CNOOC Ltd. (NYSE:CEO), announced that it too was done with B.C., and called a halt to the feasibility study that had been underway on its Aurora LNG plant on Digby Island.

Blake Shaffer, a former director of energy trading for Transalta Corp., now at the University of Calgary’s Department of Economics, said the agreement announced Wednesday is far from a done deal. It is not much more than a memorandum of understanding.

Although he agrees Alaska has some of B.C.’s advantages, he said the project’s costs would be much higher than any project in B.C.

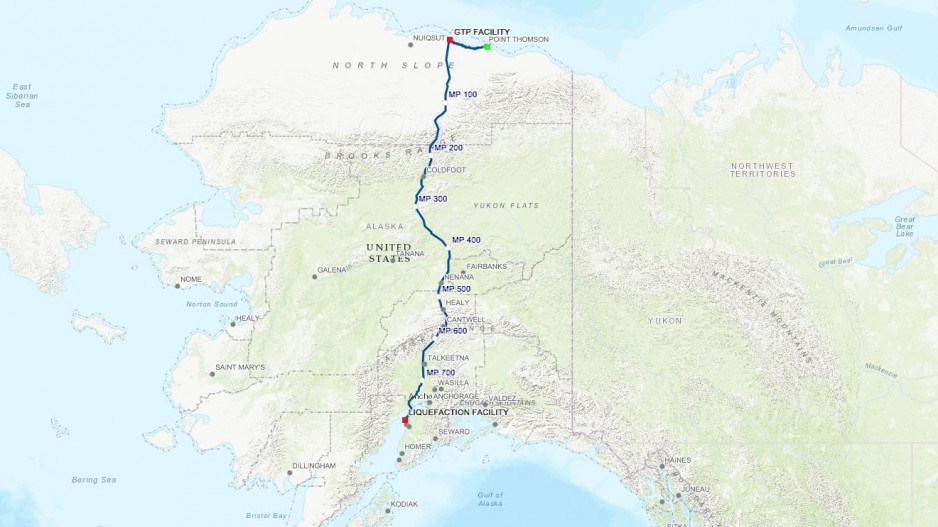

The Alaska LNG project would require a 1,200-kilometre pipeline to bring natural gas from Alaska’s North Slope to a three-train LNG plant in Nikiski in Cook Inlet.

Building the pipeline would be costly, Shaffer said, due to the higher costs of working in the remote north, and the lack of ancillary infrastructure that would need to be built – roads, processing plants, and feeder networks, all of which B.C. already has.

Traya disagrees. He said he expects the pipeline would be built with Chinese steel, which would reduce the costs.

“I can assure you that the need for U.S.-made steel for this project is not going to matter,” he said. “It’s going to be all Chinese steel, valves and engineering.”

The American Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts China will account for more than a quarter of the global growth in LNG demand out to 2040.

Its current imports of 3.5 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) are projected to grow to 11 bcf/d by 2040, s China tries to move off of coal power. Shaffer said the Alaskan LNG plant, if built, would supply 2.5 bcf/d.

He points out that B.C. projects also have Chinese partners. PetroChina, for example, is one of the partners in the LNG Canada project.

“I don’t see China buying (Alaska) LNG as a substitute for BC LNG,” Shaffer said. “I don’t see them as having an issue with scale.

“Rather, I think it’s more likely this is a sign they’re now buying North American LNG as part of a bigger strategy. I wouldn’t be surprised to see movement on LNG Canada in the not-too-distant future.”

Traya doesn’t think Canadian projects can compete with Alaska LNG, however, because the project would have the Government of Alaska as an equity partner, whereas in B.C. the government’s main role has been as a would-be tax collector.

He said the former Liberal government made a fatal mistake when it signaled to the industry that it was viewed as a cash cow, and established a special LNG tax that LNG producers don’t face in other countries.

“Why did all the B.C. advantage dwindle? It dwindled because of the rent-seeking behaviour of the province,” Traya said.

“How did the Alaska project – which was really out there and never thought to be a consideration – how did that become viable? It tells you how much fumbling and missteps happened in B.C. where companies are jumping and bailing on their projects.

“The B.C. government needs to get its head up out of the sand and realize if it doesn’t provide fiscal certainty and potentially an equity stake in LNG, it doesn’t have a project.”