In 2009, B.C. sockeye salmon sales generated just $39.2 million, thanks to the near collapse of that year’s Fraser River sockeye run.

A year later, sales hit $174.4 million, which doesn’t include all the frozen and canned sockeye that would have been sold in 2011, according to B.C.’s 2011 Seafood Industry Year in Review.

The catch – and the resulting sales – could have been much higher than that, say fisheries experts, but the 2010 returns were so unexpectedly high that it caught fisheries managers, commercial fishermen and processing plants unprepared, and a lot of fish that might have been caught and sold went up the river to spawn – about 13 million, according to one estimate.

Fisheries managers were stunned when 28 million sockeye returned to the Fraser River in 2010 – the highest return on record – and processing plants were overwhelmed with the bounty.

“In 2010, the industry was stretched to its capacity,” said Rob Morley, vice-president of product and corporate development for Canadian Fishing Co. (Canfisco). “That essentially means you have to slow how much fish a fisherman can catch.”

Thanks in part to an unusually large escapement of about 13 million fish in 2010, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is planning for another monster run this season – possibly record-breaking.

This time around, commercial fishermen and processing plants along the B.C. coast are hoping to be better prepared.

“I think we have enough capacity to harvest the fish coming back,” Morley said.

“You’re looking at an industry that’s better prepared,” said Joy Thorkelson, a spokeswoman for the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union. “The processors have been expanding their capacity on the south coast.”

This year’s return is estimated to be anywhere between seven million and 70 million fish, although there’s only a 10% chance of 70 million returning. For planning purposes, DFO is aiming for a return of 23 million, which would be the second-largest run on record.

Dennis Brown, author of the book Salmon Wars, believes 23 million is an accurate forecast.

“They’ll get a decent return this year,” he said, “but they’re not going to get a giant run.”

Despite wild swings in salmon populations and policies that have kept commercial fishermen off the water – even in years when sockeye were relatively abundant – Fraser River sockeye are still considered the bread and butter of B.C.’s seafood industry.

Chinook may fetch higher prices, but sockeye is highly valued and comparatively prolific.

In 2010, wild sockeye generated $174.4 million in sales, coho $20.5 million, chinook $18.5 million, pink $16.8 million and chum $9.7 million.

Even in 2009, when only 1.4 million Fraser River sockeye returned, sockeye generated more money than any of the other four species of wild salmon.

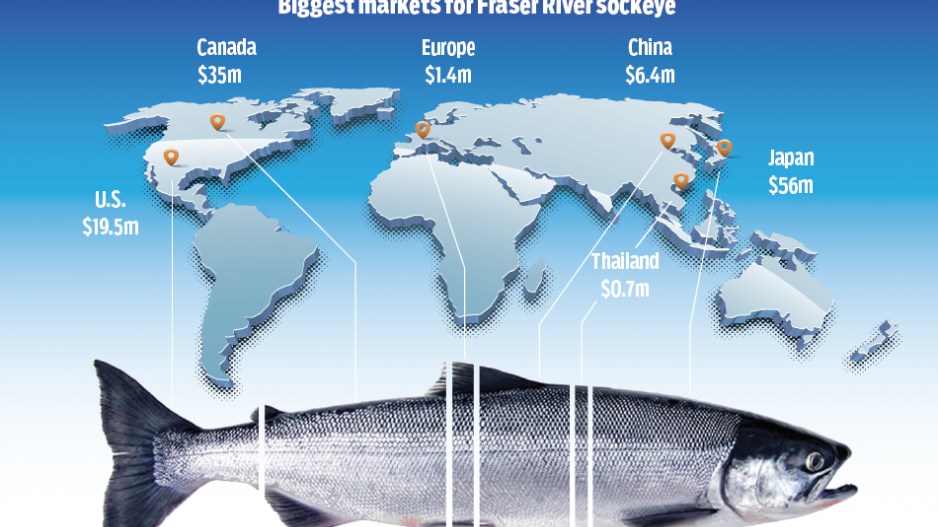

Based on sales figures from the BC Salmon Marketing Council, about 20% of the sockeye caught in B.C. are sold in Canada. The rest are sold to export markets.

Of the $174.4 million in sales in 2010, Japan alone accounted for $56 million ($18.5 million fresh, $37.5 million frozen). The second biggest export market is the U.S.

B.C.’s other major seafood industry – salmon farms – also sells 20% of its product domestically; 80% is exported. Unlike with wild salmon, however, the U.S. – not Japan – is the largest buyer, and unlike wild salmon, farmed Atlantic salmon are only sold fresh, not frozen.

Should this year’s return of Fraser River sockeye be in the 20-million range, B.C. salmon farmers expect to see their prices drop.

“An increased amount of sockeye salmon in the marketplace is going to reduce the commodity price of Atlantic salmon, similar to if the Chileans put a bunch of product on the market, then the price of Atlantic salmon overall, globally, goes down,” said Jeremy Dunn, a BC Salmon Farmers Association spokesman.

B.C.’s seafood industry generated $1.4 billion in 2010 and 2011. Salmon farming accounted for between $550 million and $560 million; wild salmon generated between $208 million and $240 million. •

If this year’s Fraser River sockeye returns are in the 30-million-to-40-million range, it’s unlikely the commercial fishing sector could cope, says retired fisheries biologist Carl Walters, an expert in fisheries stock assessments.

That many fish would likely result in large escapements, as in 2010, when an estimated 13 million fish made it to the spawning grounds. By contrast, the escapement in 2009 was one million, according to a fisheries paper produced by Simon Fraser University in 2010.

So what’s wrong with letting that many salmon return to spawn? Nothing, if you’re a fish.

It’s not so good for those who depend on them for their livelihoods, because, according to one model for sockeye population cycles, if too many fish are allowed to spawn in one year, they overwhelm a lake’s food source. Sockeye spend their first year in the lakes where they were hatched. If there are too many, they will eat all the food in a lake, leaving nothing for subsequent runs.

For more on sockeye supercycles: www.biv.com/news/fisheries