The first analysis of upstream greenhouse gases associated with industrial projects under federal environmental review is in, and it demonstrates just how inexact the calculations can be.

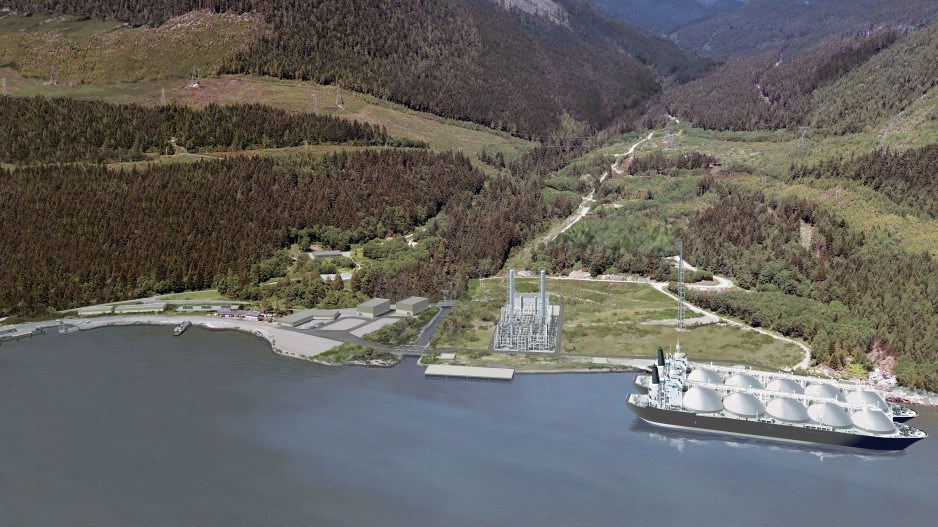

The Woodfibre LNG project in Squamish is the first major project in B.C. to have an addendum analysis on upstream greenhouse gas emissions as part of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) review process.

The potential impacts on climate change from upstream activities have not been part of federal reviews conducted by the CEAA or the National Energy Board (NEB) for oil and gas pipelines.

But in accordance with a pre-election promise by the Justin Trudeau Liberals to include climate change as part of all future NEB and CEAA reviews, an analysis now must be done that estimates the potential increased GHGs that might be associated with pipeline and other industrial projects.

Both carbon dioxide and methane are produced as part of the upstream extraction, processing and transmission of natural gas.

There are also carbon emissions generated by the liquefaction process itself, although in Woodfibre LNG’s case, they are comparatively low because it is the only LNG project in B.C. that proposes to use electric drive.

“The facility’s direct GHG emissions of 0.129 Mt/year are low compared to other proposed projects as the Woodfibre project uses electricity from the grid to drive the compressors that liquefy the natural gas, rather than using natural-gas driven turbines,” the analysis acknowledges.

The CEAA calculates that the upstream GHGs for Woodfibre will be 700 to 800 kilotonnes per year, or 17.5 to 22 megatonnes over 25 years.

The GHGs produced in the LNG process itself are relatively straight-forward to calculate. But the upstream emissions may be harder to accurately estimate, at least in Woodfibre’s case.

Unlike other projects, where the companies own both the upstream and downstream assets, Woodfibre doesn’t own any gas. It will source natural gas from a variety of producers in B.C. and Alberta.

But where the gas actually comes from can make a big difference in terms of GHG calculations.

The gas in some basins is literally cleaner, in terms of carbon content, than others. Horne River gas, for example, has a 12% carbon content, whereas Montney gas is just 1%.

Also, some natural gas processing plants use carbon capture, while others don’t – something that could dramatically affect the carbon intensity of upstream activities.

Moreover, some gas fields in B.C. will become electrified, meaning they will get their electricity from clean hydro power, whereas others will burn natural gas to power the extraction, processing and transmission of gas. And while some processing plants currently don’t have carbon capture, they may in the future.

In other words, the actual carbon intensity of the gas that Woodfibre will use itself could vary widely, depending on where it comes from, and not even Woodfibre knows where it will source its gas.

“Estimating GHG emissions from upstream stages with greater accuracy would require knowledge of the facilities producing and processing the natural gas and their GHG emissions,” the CEAA report states.

The CEAA relied on the Environment and Climate Change Canada for modeling to try to come up with a best guess on upstream GHGs for Woodfibre. It also relied on studies from the Pembina Institute and the B.C. government.

“If you accept the assumptions, they may be correct,” said Byng Giraud, Woodfibre LNG’s vice president of corporate affairs. “But you have to accept the assumptions.”

He added that, given the small scale of Woodfibre, it may well be the case that it adds no additional GHGs at all because it would not require any new wells to be drilled. It will simply be buying some gas that is already being produced for the domestic market.

“Given the size of our facility, it is arguable that we actually don’t create any new production,” he said.

Giraud said the company will study the CEAA GHG analysis over the next few week and respond to it. The public now also has a chance to respond to the study during a public comment period that runs until March 1.

Giraud expects it will take at least three months before it the CEAA makes a final recommendation on its $1.7 billion project. He said the company expects to make a final investment decision sometime this year.