As ghost towns go, Kitsault must surely be one of the more well preserved.

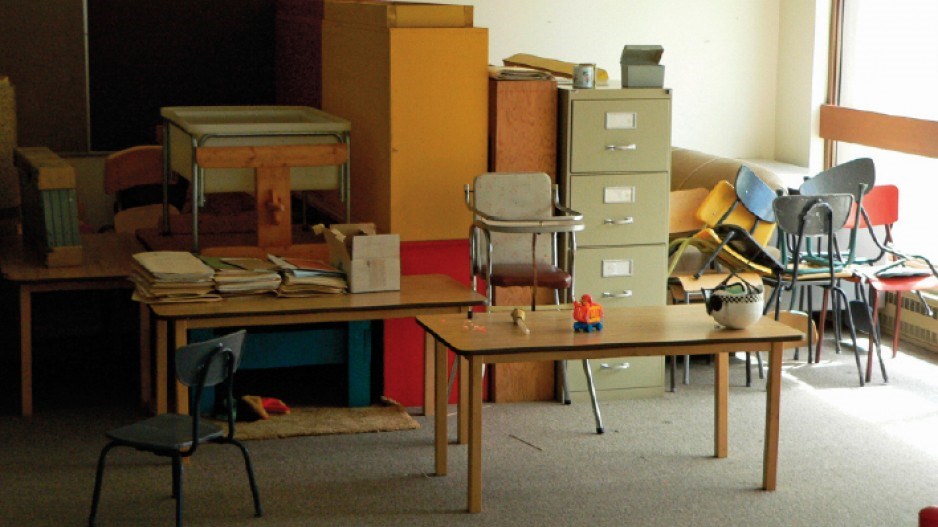

Built in 1979 and abandoned three years later when a molybdenum mine shut down, the village is vacant, except for maintenance staff tasked with fixing roofs and roads, mowing grass and generally keeping the village from dissolving in the rain.

When American millionaire Krishnan Suthanthiran bought the ghost town in 2005 for US$5.7 million, his vision was to see Kitsault become an "eco-village" for scientists and artists – but no one moved there.

Idyllic though it may look and sound, Kitsault is remote. Located at the head of Alice Arm near the Alaskan Panhandle, it's a three-and-a-half hour, 183-kilometre drive along a dirt road to get to the nearest city – Terrace – and its rainfall is measured in metres, not millimetres: up to two metres per year.

Suthanthiran, who made his fortune in the medical device business, is now trying to position Kitsault as a ready-made town to serve the oil and gas industry.

He was busy last week floating a trial balloon in Ottawa and Vancouver to see if there is any interest from governments, First Nations and the oil and gas industry in developing Kitsault into an energy hub.

His plan calls for gas and oil export terminals, a liquefied natural gas plant – even an oil refinery.

"Our goal is to reach out to the users – customers in Asia and other parts of the world – and the energy companies and the First Nations communities and see what can be done," he told Business in Vancouver

With 100 single-family homes, 150 apartments, a school, pub and community centre, the village could handle an instant influx of up to 1,000 people. It just lacks an industry.

Suthanthiran doesn't believe his latest vision for Kitsault is an about-face from his original plans to develop Kitsault as a kind of eco-refuge.

"Our plan originally was to bring economic activity to the town," he said. "The economic activity is to populate the town with people. It's not really inconsistent."

Suthanthiran said Kitsault has several natural advantages for developing an LNG plant and export terminal:

•it's a ready-made town;

•it's connected to BC Hydro's grid;

•it's on tidewater; and

•it could support a marine terminal dedicated to gas or oil exports.

Moreover, he said, plans for a natural gas pipeline from the Chetwynd area to Prince Rupert route it through Kitsault.

"You're already coming through Kitsault and taking it from there to Kitimat or Prince Rupert. What we're saying is we can terminate it in Kitsault. You have the infrastructure, you've got the land, and you can build more houses, more apartment buildings."

In fact, the Kitsault route is only one of three possible options being considered by Spectra Energy (NYSE:SE) and its partner, BG Group PLC, for a new pipeline from the Chetwynd area to Prince Rupert.

Any pipeline coming into Kitsault would cut through Nisga'a First Nation lands, so getting Nisga'a co-operation would be key.

Suthanthiran said he has initiated talks with the Nisga'a and other First Nations.