A controversial ocean fertilization experiment off the coast of Haida Gwaii may well boost salmon stocks, but verifying the levels of carbon sequestration in order to sell carbon offsets would be virtually impossible, according to a carbon expert.

The Haida Salmon Restoration Corp. has come under fire for what is being described as an uncontrolled experiment in ocean fertilization.

Earlier this year, in partnership with maverick American entrepreneur Russ George and with funding from the Old Massett Village council of the Haida First Nation, the company dumped 100 tonnes of iron sulphate into the ocean off coast of Haida Gwaii in international waters.

The project has a two-fold objective: boost salmon stocks by fertilizing the ocean, and sell carbon offsets for the carbon capture that would occur.

When there is a phytoplankton bloom, about 70% will be consumed by zooplankton, which in turn feed fish all the way up the food chain to salmon and whales. Roughly 30% of the phytoplankton will die, however, and when it falls to the ocean floor, it has the effect of storing vast amounts of carbon dioxide – a greenhouse gas.

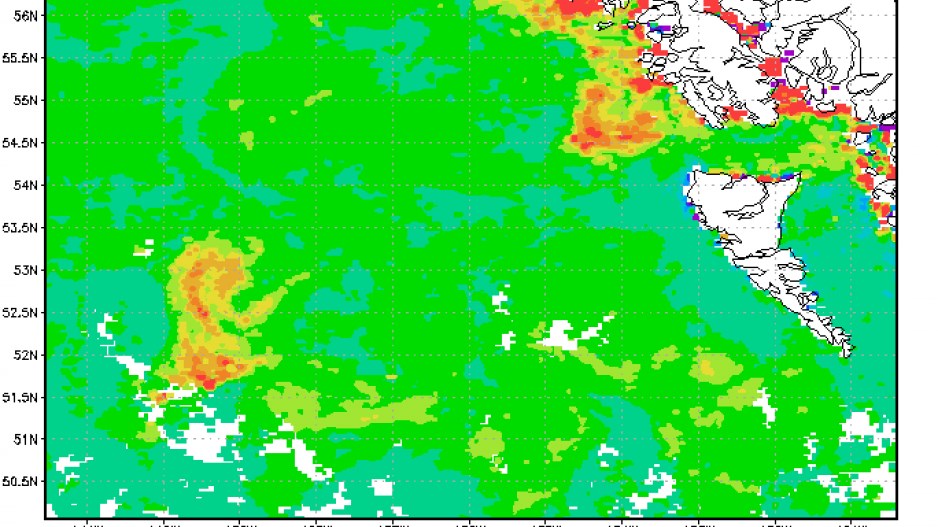

Satellite imaging shows there is a large plankton bloom now occurring in the area that was fertilized.

Robert Falls, founder and chairman of ERA Carbon Offsets Ltd. (TSX-V:ESR), does not doubt that the iron will ultimately boost fish stocks, and believes that carbon sequestration in oceans could become an important part of the battle to reduce greenhouse gases.

But he doesn’t think there’s much of a business proposition for selling carbon offsets for ocean fertilization projects.

“I don’t know how you sell carbon offsets without a validated and verified methodology,” Falls said. “The challenge of measurement and verification is significant. And there’s the social licence challenge – people just don’t like folks monkeying with the oceans.”

Falls said it is tough enough to measure the carbon sequestration that occurs in trees – in oceans it would be virtually impossible to distinguish from the naturally occurring sequestration.

Phytoplankton blooms occur naturally in the ocean when storms blow iron-rich soil into the oceans from desserts, and it has even been suggested that volcanic ash from an eruption in Alaska in 2008 caused a plankton bloom that led to the massive returns of Fraser River sockeye salmon in 2010.

That hypothesis was based in part of the research done by Roberta Hamme, an oceanographer with the University of Victoria.

Hamme said it would be difficult for George and the Haida Salmon Restoration Corp. to prove that ocean fertilization caused the current phytoplankton bloom.

“This region has eddies with naturally iron rich waters, so it is difficult to distinguish naturally high productivity regions from any artificially created one without more information,” Hamme told Business in Vancouver.

“I haven’t seen real evidence that the iron addition caused a bloom, but this is difficult to check without details on the time and location of the release.”