Bankers, economists and energy executives will be in Vancouver next week for the Pacific Energy Summit, where one of the scheduled sessions asks: “The Golden Age of Gas: How Far Can It Take Us?”

According to David Hughes, a former Geological Survey of Canada scientist, the answer to that question is: not nearly as far as the oil and gas sector claims.

“The jury’s out, but it would seem that projecting a 40-year life is wildly optimistic,” said the B.C.-based geoscientist, who is now a fellow with the Post Carbon Institute.

In his recent study, “Drill, Baby, Drill,” Hughes concludes North America’s natural gas production from shale is a bubble, with most of the gas being produced in the first two or three years of a well being fracked and then rapidly declining.

According to Hughes, some of the best shale plays in the U.S. – like the Haynseville in Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas – are already in decline.

“If you look at the Haynesville, I’d call it late middle-aged, and it’s only four years old,” Hughes told Business in Vancouver.

Noted Simon Fraser University energy economist Mark Jaccard puts Hughes’ predictions in the same camp as peak oil prognostication.

“The earth’s crust is chock-a-block full of hydrocarbons in different forms, and humans are very good at innovating ways to extract these for human use,” Jaccard told Business in Vancouver. “The ‘Global Energy Assessment’ [2012] provides the most recent estimates, and it blows the peak oil, peak coal and peak gas people out of the water.”

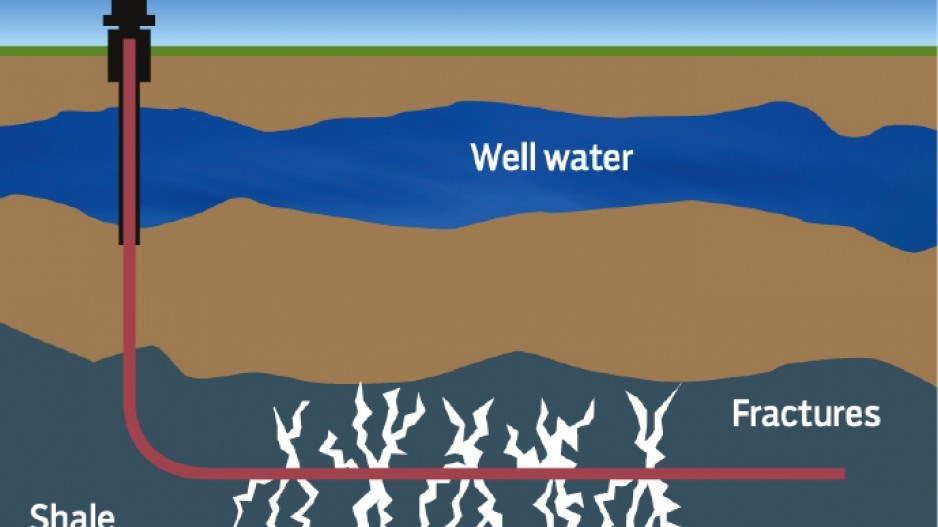

Large-scale extraction of gas trapped in shale rock became practical only about a decade ago, thanks to advancements in horizontal drilling and multi-stage fracturing, so there’s not enough historical data yet to be able to predict how long shale reservoirs can remain productive.

Hughes analyzed production data from 65,000 wells in 31 shale plays in the U.S. and concluded the wells are producing 80% to 95% less after three years than when they were first connected to the pipeline.

It’s not just geology that creates shale bubbles, according to Hughes – there are regulatory incentives, as well. He pointed out that when a good deposit is discovered, companies rush in and try to lock up as much land as possible.

“There’s a leasing frenzy. Those leases come with drilling commitments. So you have to drill in order to hold them. So the leasing frenzy is followed by a drilling boom.”

With gas prices so low, producers target “sweet spots” to maximize returns. This creates a sudden abundance of gas, and a process of diminishing returns sets in as companies are forced to invest more and more in less productive wells to address field decline.

“The overall field decline in a play like the Haynesville is 52% per year,” Hughes said. “So 52% of field production has to be replaced with new drilling each year. As the well quality goes down, you need more wells to offset fuel decline. It’s what you call a drilling treadmill.

“You need to basically inject about $7 billion a year of capital into drilling just to keep production flat.”

How shale gas reserves could play out in B.C.

In northeastern B.C., the major shale formations are the Montney near Fort St. John and Horn River near Fort Nelson. Because the Montney is more silt than shale, with good permeability, it could have a lifespan closer to conventional gas plays, Hughes said – 30 to 40 years.

But ultimately, he said, the shale gas industry is still too new to make any solid predictions.

Marc Bustin, professor of petroleum and coal geology at the University of British Columbia, concedes there is still a lot to learn about shale formations. But he doubts the oil and gas industry would be investing billions in it if it didn’t think there was a long-term return.

“So if it is a bubble, it is an enormous bubble,” he said.

He points to the Barnett formation in Texas, which has been producing gas since the 1980s.

“They have a steep decline rate, there’s no question about that,” Bustin said. “The bottom line is if it wasn’t economic, they wouldn’t continue to do it.”

As for B.C.’s natural gas reserves, EnCana Corp. (TSX:ECA) has estimated the Horn River basin alone has about 500 trillion cubic feet of gas.

“These are enormous numbers,” Bustin said. “How much we can actually produce from a given well might be a little bit questionable, but that the gas is there, no technical person I think would question that.”