It was shaping up to be a good year for liquefied natural gas (LNG). It was the talk of the town at the outset of 2014, especially in Victoria, where Premier Christy Clark was singing LNG’s praises.

B.C.’s LNG riches were going to benefit British Columbians for decades to come. They were going to pay down a provincial debt that’s headed north of $70 billion. The BC Liberals’ LNG initiative, Clark figured, would generate a cool $1 trillion in economic activity for the province and create 100,000 new jobs. According to the Liberals’ February 2014 throne speech, LNG was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Not only was it going to enrich B.C., it was also going to help wean China and adjacent emerging Asian economies off their less environmentally friendly coal-powered energy addiction.

In short, B.C. LNG was going to change the world.

B.C.’s finance minister had his own calculator in optimistic overdrive.

Among Mike de Jong’s early 2014 estimates for a single B.C. LNG plant after a decade of production: “up to $1.4 billion in LNG tax alone.”

Skeptics and other negative naysayers, he said, “are going to find it harder and harder over the coming years to deny that this is happening.”

But Clark’s “transformative opportunity” for the province was transformative for more than just B.C. 2014 confirmed that it was a transformative opportunity everywhere.

By year’s end, the promise of the new sector had gone from world-changing aspirations to a more modest outlook of bumping up provincial revenue and what the government’s October throne speech stated would be helping to “maintain … the same world-class services we rely on.”

With the weakening promise of LNG came a loss of confidence among British Columbians.

In a recent Insights West-Business in Vancouver survey only 28% of respondents said the provincial government was doing a good job in handling energy, pipelines and liquefied natural gas, down eight percentage points from May.

LNG – BIV’s newmaker of the year – opened 2014 with a baker’s dozen of projects ranging from Aurora LNG’s 24-million-tonne-per-year proposal for Grassy Point north of Prince Rupert and Kitimat LNG’s five-million-tonne operation at Bish Cove, Kitimat, to Pacific NorthWest LNG’s Petronas-led plan for a 12-million-tonne LNG export facility on Lelu Island, near Prince Rupert’s Port Edward.

By year’s end, the total of proposed projects had hit 18. But the number of those with any realistic chance of getting their multibillion-dollar plans to market in the face of energy price volatility and amped-up international competition was shrinking. LNG market analysts like former Geological Survey of Canada scientist David Hughes figured a couple at most, and their game plans relied on involvement from sovereign states seeking long-term energy security, not just profit.

During 2014, LNG B.C.’s golden-boy image also took it on the chin from the global marketplace’s new competitive reality.

Natural gas was going global. LNG technologies, which allow it to be shipped globally like oil, coupled with the fracking/horizontal drilling revolution that unlocked vast new reserves of oil and gas, were seeing to that.

“What we’re right in the middle of [now] is the globalization of the natural gas business,” said Barry Munro, EY’s Canadian oil and gas leader. “LNG is making that possible, and that’s really exciting.”

Exciting, yes; easily exploited by B.C., no.

Especially considering that the province is starting its LNG industry pretty much from scratch.

The reality of that in late 2014 compared with the outset of the year, Munro said, is that “some of the optimism we would have sensed a year ago has been replaced by the reality of how tough and competitive global market forces are. We are doing a highly capital-intensive project on a greenfield [from scratch] basis in a highly competitive global marketplace. There are lots of dynamics globally, and what we sometimes forget from a B.C. perspective is that we’re trying to create an industry where there isn’t one.”

Another reality check for LNG, according to Munro, is that demand is not infinite.

A year ago excitement around the prospects for B.C. LNG was based in large part on that skewed perspective, he said.

“There is a much better appreciation today that that’s probably not the case.”

He added that global competitive factors facing the B.C. industry have also been “put under a finer microscope.”

B.C.’s proposed LNG industry is now in tough competition with hungry up-and-comers as well as global big boys.

Key contenders in the hungry-up-and-comers category: East Africa; in LNG’s global big boys division, Australia, soon to be rivalling Qatar for the title of global LNG export champ; and Russia, which signed two major deals in 2014 to supply China with natural gas.

But Munro said the province’s biggest competitive threat comes from the U.S.

Its advantages include established pipeline and import-export infrastructure in Gulf state natural gas hot spots and the depth and diversity of that area’s labour force.

What it added during 2014 and what has made it such a serious competitor, according to Munro, was the unexpected acceleration of its regulatory process and a newfound political will to execute the turnaround from fossil fuel importer to fossil fuel (LNG) exporter.

B.C. has no shortage of political will; but the regulatory process in 2014 had far less momentum.

Clark’s Liberal government finally provided certainty on B.C.’s LNG tax but took until the fall to release its details.

That’s a good news/bad news scenario.

The good news: industry cost certainty in one area where there was previously speculation and a tax rate that was reduced from original proposals.

The bad news: B.C.’s LNG tax is only one in a long inventory of government-instituted costs for proponents with ambitions to do business in B.C.

As David Keane, president of the BC LNG Alliance, pointed out to BIV following the October announcement outlining the tax regime’s details, the already significant tax load borne by B.C.’s LNG industry got heavier.

“Now we will be paying an LNG tax, a carbon tax and … we will also have to purchase carbon offsets, we will be paying PST, GST, municipal property taxes, payroll taxes and, of course, corporate income taxes at both the federal and provincial levels.”

In addition to the 1.5% tax on an LNG project when production begins, which rises to 3.5% after capital costs are recovered, Victoria rolled out tough greenhouse gas regulations covering the LNG industry.

The second-tier 3.5% tax rate, half the 7% originally floated earlier in the year, was likely reduced in response to Russia’s US$400 billion deal signed in May to supply China with natural gas and to the rising chorus of complaints about regulatory processes and costs in Canada from major proponents like Petronas chief executive Shamsul Abbas.

By year’s end, Petronas hedged its bets on its B.C. project. It announced December 3 that in its ongoing review of Pacific NorthWest LNG’s economic viability and in view of rapidly falling global oil prices it was deferring the project’s final investment decision (FID).

BG Group had made a similar announcement at the end of October. The Britain-based project operator of Prince Rupert LNG, originally scheduled to make its FID in 2016, delayed that decision to at least 2017.

What has not changed for B.C. LNG during 2014 are the challenges of oil and natural gas price volatility and securing First Nations’ involvement and approval in the sector.

Hughes, the president of Global Sustainability Research and the author of Drill, Baby, Drill, recently released Drilling Deeper: A Reality Check on U.S. Government Forecasts for a Lasting Tight Oil and Shale Gas Boom.

The report reviews the dozen major shale gas plays that account for 82% of the tight oil production and 88% of the shale gas production in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts through 2040.

It estimates that shale gas production from the top seven of those plays will underperform the EIA’s forecasts by 39% from 2014 to 2040 and will be about one-third of those forecasts by 2040.

According to Hughes, that’s primarily because natural gas reserves accessed through fracking are depleted faster than those tapped using traditional methods. The price of North American natural gas through 2040, he said, will therefore inevitably rise and production will drop.

Coupled with the current nosedive in oil prices, that’s bad news for producers who need sources of cheap North American natural gas to sell at a higher price in Asia to make their LNG projects viable in the long term.

“The fact that no company has committed yet [to a B.C. LNG project] tells you something about B.C.’s prospects,” said Hughes. “The myth that natural gas will be cheap forever is indeed a myth.”

The issue of First Nations involvement likewise remains significant for any natural gas project in B.C., including Kitimat LNG.

Considered to be a front-runner in the race to bring a B.C. LNG export facility to market, it too faces numerous hurdles before it reaches the FID finish line.

One of those hurdles was removed December 15, when Chevron’s(NYSE:CVX) co-venture partner Apache Corp.(NYSE:APA) agreed to sell its Kitimat LNG stake along with its interest in Western Australia’s Wheatstone LNG project to Australia’s Woodside Petroleum Ltd. for US$2.75 billion. Apache had announced in July that it planned to sell its 50% stake in Kitimat LNG.

Remaining hurdles, according to Chevron-Kitimat LNG spokeswoman Gillian Robinson, include establishing a clear, competitive and stable fiscal framework and gaining additional First Nations support.

The complexities of engaging First Nations and aligning pipeline and other project interest with theirs, said Mary Hemmingsen, KPMG national sector leader, LNG, power and utilities, is a challenge for B.C. LNG proponents that other jurisdictions don’t have.

Recent passage of legislation to establish the Nisga’a Nation as the primary property taxation authority over Nisga’a lands is a major first step in that process, at least as it relates to the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Project’s proposed 900-kilometre pipeline project, which is key to the Petronas proposal.

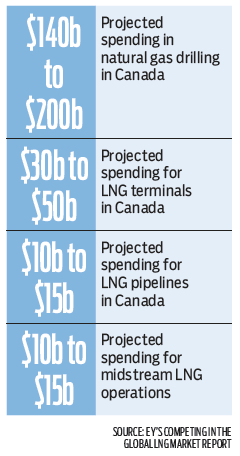

Munro said gaining First Nations support, one of five critical competitive factors facing Canadian and B.C. LNG projects outlined in his Competing in the Global LNG Market report, remains one area where Clark and her government need to play a leading role in helping project proponents gain First Nations support.

Another, he said, is cheerleading.

“This is a new industry for Canada and a strategically important one for the country, not just B.C., and the reality is that, given the size of investment, government had to play some role in leadership. … [Cheerleading] is maybe what’s required when you are trying to stand up a new industry.”

Despite the increasingly uncomfortable realities delivered to B.C.’s LNG dream during 2014, head cheerleader Clark remains optimistic.

The premier said in an email response to BIV that the province is still “very much poised to capitalize on a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

She added that when Petronas makes its final investment decision, “it would be an investment of $36 billion. That’s equivalent to the total contribution of mining to Canada’s GDP – in a single project.”

Clark conceded that building a new industry from scratch is not easy and that industry, not the government, will make the final decision on whether B.C. is the right place to build that industry.

So Newsmaker 2014 needs all the cheerleading it can get, because for the promise of LNG to keep up its momentum in 2015, a lot of dominoes have to fall in the right direction for this province, a high-cost producer that is already late to the global LNG party.•

Newsmaker 2014's shifting business prospects in quotes |