In 2013, when oil was selling for US$100 per barrel and oil pipeline proposals like Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain were getting a rough ride from regulators, environmentalists and First Nations, Alberta Energy provided $1.8 million to study an oil-by-rail proposal that seemed ludicrously ambitious.

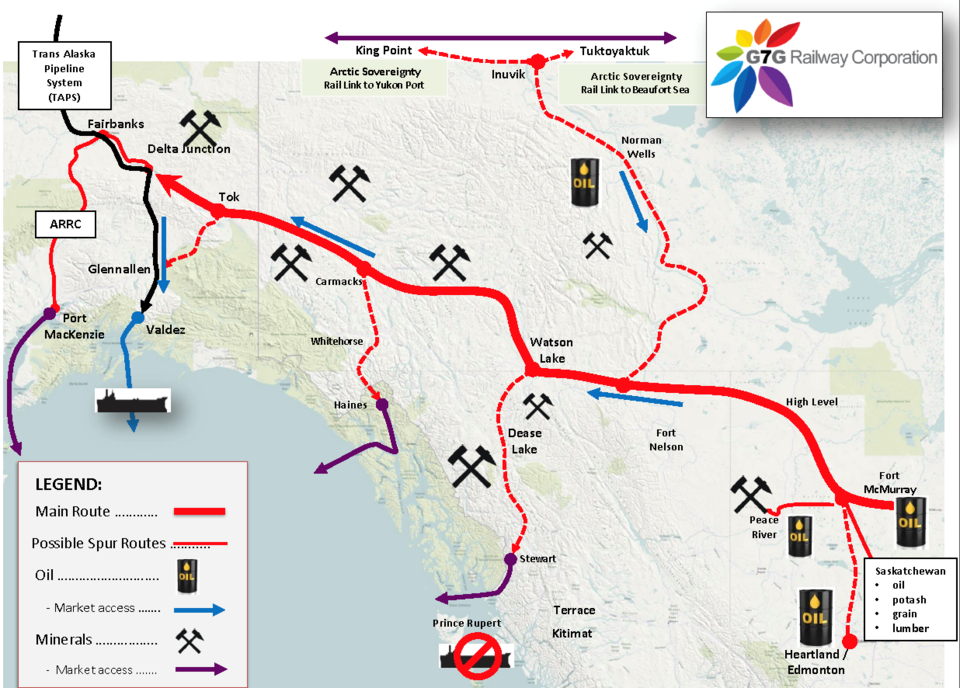

Rather than try to build a pipeline to tidewater on the “pristine” west coast of B.C., what if a new railway could be built from northern Alberta to Delta Junction in Alaska, where undiluted bitumen could then be unloaded, diluted and moved on the underused Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) to Valdez?

Not just any railway either, but a double-tracked electrified railway that could move one million barrels of oil per day, as well as iron ore and other minerals from potential new mines in northern B.C. and the Yukon.

It would solve Alberta’s land-locked oil to foreign markets problem, and it would solve Alaska’s underused TAPS problem. It would also solve the Yukon’s problem of mineral deposits that can’t be developed into mines due to a lack of transportation infrastructure.

But given the opposition that pipelines in B.C. have received from First Nations, how could such a project get the consent of First Nations in Alberta, B.C., the Yukon and Alaska for a 2,440-kilometre double-tracked railway carrying bitumen from Alberta’s oilsands?

Matt Vickers, a Tsimshian-Heiltsuk business consultant from Vancouver and partner in G7G (Generating for Seven Generations), says the Alberta-to-Alaska railway project has letters of support from every Indigenous group along the proposed railway corridor but one: the Fort Nelson First Nation.

Which is why the proponents are now recommending a route that would largely bypass B.C.

One of the selling points, for First Nations, is that they wouldn’t be just granting permission for the railway to be built, but would be equity partners in the project.

The Alberta-to-Alaska railway builds on an earlier $11 billion proposal considered by the governments of Alaska and Yukon, which had proposed in a 2007 study that a railway be built from northern Alberta to Alaska, via northern B.C. and Yukon, to facilitate the development of new iron ore and other mineral mines.

“Here’s their opportunity to connect to the lower 48 states, here’s their opportunity to save TAPS and the port in Valdez,” Vickers said, “and the cost of living for all those people in the north is going to change overnight.”

Vickers and his partners with G7G worked with the engineering firm AECOM (NYSE:ACM) on an initial proposal and pitched it to Alberta Energy, which allocated $1.8 million for a pre-feasibility study.

That study, concluded by the Van Horne Institute in 2015, estimated a conventional double-tracked railway with a capacity of one million barrels per day (bpd) would have a capital cost of $27 billion.

To put that in perspective, the Energy East pipeline, which also would have moved one million bpd, was estimated to cost $15 billion, but would have moved only oil, no other commodities.

While the Alberta-to-Alaska railway was originally conceived as a conventional diesel-powered system, G7G is now considering an even more ambitious proposal: making the railway “green” by going electric.

Using a system developed by Elways in Sweden that uses conductive charging, the proposed electric system would charge the batteries used to power locomotives while they are moving, eliminating the need for them to stop to recharge.

“Initially we talked about conventional rail,” Vickers said, “but right now we’re seeing that there is the possibility of electric rail.”

The “indy drive” that is being considered for the project is proven technology, said Ward Kemerer, one of G7G’s partners.

“I’m just taking elements from here, here and here and putting it all together because they’re all off the shelf now,” Kemerer said.

He pointed to Elon Musk’s recently unveiled Tesla electric semi truck as an example of where the transportation industry is moving – electrification.

But who would finance such a grandiose plan?

“We’re fairly close to securing the financing now,” Vickers said, adding he hopes an announcement on financing will come early in the new year.

He would not say who the major financing partners would be, but confirmed some of the financing might come from China.

“I can’t be disclosing any of that right now,” Vickers said. “I can share, obviously – because it’s public knowledge – we went to China, July, August of last year, and talked to a number of the big state-owned enterprises and came back with a memorandum of understanding with respect to doing joint ventures with the First Nations to do the rail project. And there’s a number of big Canadian pension funds that we’ve been talking with.”

When the project was pitched to Alberta Energy in 2013, oil prices were double what they are now, and no new Canadian pipelines had yet been approved.

Since then, the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion was approved, and the Keystone XL pipeline – nixed by the Obama administration – is now back in the regulatory approval process, although hurdles remain.

However, even if those pipelines get built, Vickers said there is still enough potential growth in Alberta’s oilsands to justify a new oil-by-rail project to Alaska. As he pointed out, it’s not just oil prices constraining oilsands expansions, but a lack of pipeline capacity.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers estimates Alberta oilsands production will grow by 1.2 million bpd by 2030, requiring an additional pipeline capacity of 1.3 million bpd.

“If all the pipelines went ahead, even Enbridge, there’d still be a need for more capacity,” Vickers said. “The oilsands – the small, medium-sized markets producing oil – they can’t get space on pipelines. It’s just the big companies that do, so they still need a method of getting their product to market as well.

“And I think, most importantly, we’re an all-commodity infrastructure project – not just oil.”

Under G7G’s proposal, bitumen from Alberta’s oilsands would move by rail in undiluted form, which reduces environmental hazards in the event of a spill, because undiluted bitumen quickly solidifies.

At Delta Junction, Alaska, it would be unloaded, diluted with condensate and then moved along the TAPS to Valdez.

The TAPS pipeline has been underused for years. Oil production in Alaska peaked in 1988 at two million bpd. Less than 500,000 bpd now moves through TAPS, so the Alaskan government is keen to see new uses for the pipeline and its terminal at Valdez.

“When it hits 375 [thousand bpd], it can’t flow anymore,” Vickers said, “so we’re really a saviour for this pipeline.”