On December 9, Seaspan Ferries Corp. took delivery of the first of two new hybrid cargo ferries.

There is some irony here: the new vessel, which can run on diesel, liquefied natural gas or battery power, was not built by Seaspan Ferries’ parent company in Vancouver – it was built in Turkey. So were some of the new tugboats Seaspan has built in recent years.

Seaspan Marine Corp. also had to withdraw from competitive bidding when BC Ferries issued a bid request for new hybrid vessels that it has ordered. The ships are being built in Poland.

It’s not that Seaspan doesn’t have the expertise to build its own ships – it’s just maxed out, with all hands on deck building new vessels for the Canadian Coast Guard.

“You’ve had to see us pass on a couple of opportunities, including potentially building the BC Ferries intermediate class that was built over in Poland, as well as our sister company Seaspan Ferries’ hybrid vessels that are now being delivered,” said Brian Carter, president of Seaspan Shipyards. “We just do not have the capacity to do it because we’re very focused on getting the federal shipbuilding correct and on its feet.”

The outsourcing of shipbuilding by Seaspan and BC Ferries to Turkey and Poland underscores just how badly the Canadian shipbuilding industry has languished in recent decades – a trend the federal government is trying to reverse through its National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS).

Canada’s shipbuilding industry has gone through boom-and-bust cycles for more than a century, with shipyards keeping busy for a few years on government contracts, thanks to federal subsidies, and then winding down until the next big contract, which can sometimes take decades.

“When I started in the industry here in the early ’70s, we had half a dozen very capable shipyards in the Lower Mainland,” said Robert Allan, president of Robert Allan Ltd., which employs 85 engineers and naval architects for ships built around the world. “But there was demand, and that demand was fuelled in part by the subsidy.”

In the earlier part of the 20th century, B.C. shipbuilders thrived, building fishing boats, tugboats and barges. The industry flourished again during the Second World War and in the postwar period. But it has languished since the 1990s. One attempt to revitalize B.C. shipbuilding in the 1990s – the NDP’s fast ferry program – was an expensive failure.

“We haven’t built ships for a while,” said Chuck Ko, president of Allied Shipbuilders, which employs 80 people, doing mostly ship repairs. “We haven’t been able to capture a project. We haven’t had the continuity of work to basically keep ourselves in a leadership position for building ships.”

Continuity of work is the problem that the national shipbuilding strategy is intended to address. It is a long-range plan intended to use Canada’s procurement powers to acquire the new ships Canada needs, while giving Canadian shipbuilders decades of bankable work by building combat vessels for the Royal Canadian Navy and vessels for the Canadian Coast Guard.

Launched in 2010, it identified two Canadian shipyards to build all the ships Canada will need in the coming decades. Irving Shipbuilding Ltd. in Halifax was chosen to build combat ships for the Canadian navy. Seapspan was selected to build non-combat ships for the coast guard.

Over a 30-year period, it calls for 50 large ships and 115 smaller vessels to be built in Canada. The non-combat package is valued at about $8 billion.

“What that’s allowed them to do is level-load those facilities for the next 20 or 30 years so that, by the time they’re through rebuilding the existing fleet, it’s time to start looking at doing it again, because the useful life of a ship is about 25 years,” Carter said.

For Vancouver, the national shipbuilding strategy has provided a significant economic boost, generating hundreds of millions in new investment and several hundred new jobs at Seaspan.

According to the Conference Board of Canada, Vancouver is expected to lead the country in economic growth in 2016 and 2017, partly due to activity at Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards.

Seaspan will build up to 17 vessels over the next 10 to 15 years.

The projects announced to date – seven vessels – total about $3.3 billion. The first order was for three 64-metre offshore fisheries science vessels, one offshore oceanographic science vessel, two 175-metre joint support ships and one 150-metre polar icebreaker.

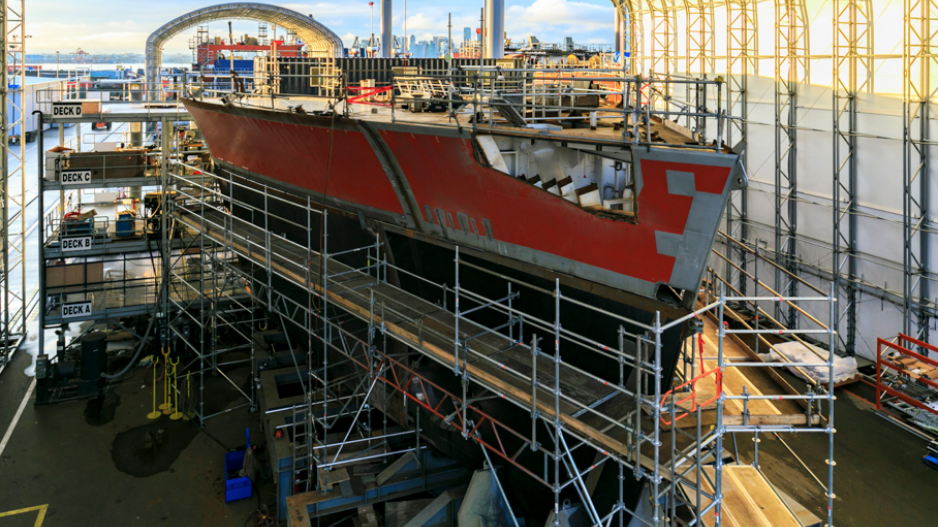

The first of three coast guard offshore fisheries science vessels, the Sir John Franklin, is nearing completion and is expected to hit the water in summer 2017. Work has already started on the second vessel. Winning the contracts required a $155 million modernization at Seapsan’s Vancouver Shipyards. That modernization has resulted in a shift in the way the ships are built, using an assembly line process in which 37 distinct “blocks” are built, assembled into nine major blocks and then pieced together.

“This is the modern shipbuilding approach,” Carter said. “It’s a departure from what Canada’s done in the past. And the national shipbuilding strategy is what allows for this to happen because we have a stable and predictable backlog of work.”

Before the expansion, Seaspan employed 150 tradespeople and a 50-person management team. Since 2012, the company has hired 375 management staff and 400 new trade workers.

“We pressed ‘go’ on February 14, 2012, and we’ve hired 775 people since then,” Carter said.

Through the NSPS, the federal government hopes not only to build ships, but also to rebuild Canada’s shipbuilding industry.

“There will be a point in time, probably after the icebreaker, in which about half our capacity will be dedicated to the federal fleet renewal, and then the other half will be available for either commercial sale or possibly an export of a ship that we built for the government of Canada to another government,” Carter said. “Our goal, as a non-combat shipbuilder, is to create a sustainable business that doesn’t rely entirely on the government shipbuilding work to be successful.”

But Allan said Canadian shipbuilders face some pretty stiff competition. Canada is a small domestic market. There are only so many ships that federal or provincial governments need.

And while the NSPS may be good for Irving and Seaspan, Allan thinks it’s a stretch to think that it will rebuild Canada’s shipbuilding industry when Canadian shipbuilders are competing with countries like South Korea and Turkey. “Our Turkish client, building 25 tugs a year, [is] an absolute production machine, and they do superb work,” he said. “Yes, their labour costs are less expensive than here, but the quality of work that they do is second to none. It’s as good as I’ve seen anywhere in the world, and so why would you go anywhere else?”