When David Demers kicked off his tech career at IBM (NYSE:IBM) in the 1970s, he intended to stick around for only a year or two before finding a more “entertaining” job.

“I’m sure that they [IBM] had a good chuckle because probably most kids my age had that theory,” recalled the CEO of Westport Innovations (TSX:WPT; Nasdaq:WPRT).

“But they just kept dangling interesting things to do.”

Demers worked on everything from the first laser printers to the first email system in Western Canada. He never remained on a project for more than nine months before the company dangled another carrot in front of him.

That tendency to stick around at a tech company that keeps filling his plate with fascinating innovations has yet to wane.

Demers spent 12 years at IBM before deciding the time was right to move on and establish an early-stage venture capital consulting group that went looking for startups in Vancouver.

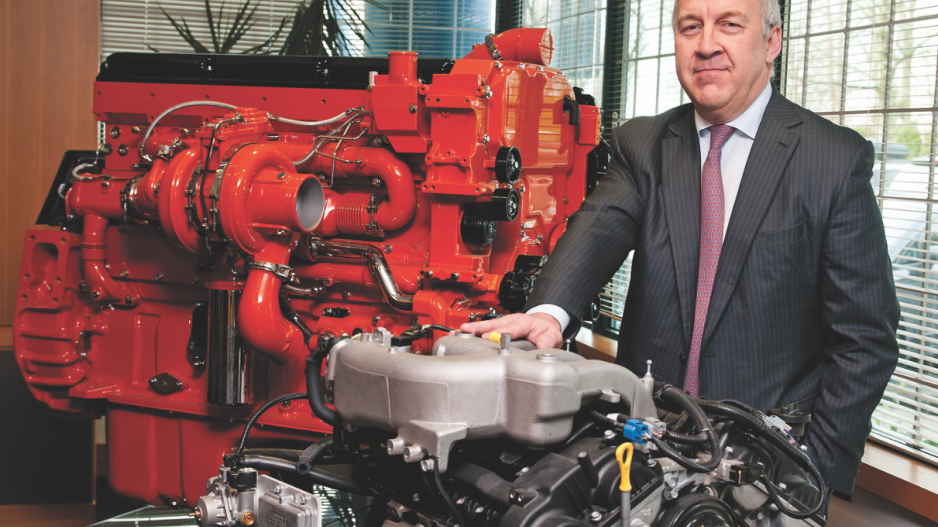

He co-founded Westport in 1995 after partnering up with University of British Columbia researchers working on compressed natural gas engines, and he’s served as its CEO for 20 years.

The original plan was for Demers to help get the clean-tech company established before recruiting a new CEO to run the business. But even though the company has not posted a profit since its founding, that new CEO has yet to be recruited.

“We’re not going to leave our employees and our investors in the lurch, right. I’m not about to walk away when we’re facing challenges,” he said. “That said, it’s long overdue that someone else take over, and I’m sure my board someday is going to say, ‘We have that successor and let’s move on.’”

But the fact is – much like his time at IBM – he likes his job and doesn’t want to leave.

Growing up in Saskatchewan, where “it was very clear farming was a really dumb thing to want to do,” Demers was eager to pursue something he had a passion for.

Continuing to work on his twin uncles’ farm wouldn’t cut it, but like many young people he hadn’t quite set his mind to what his career would be.

While earning a joint degree in physics and law from the University of Saskatchewan, Demers would trek to Calgary during the summers to work at an IBM computer lab that assisted companies operating in the oilpatch. It was an experience that shaped the rest of his career.

“I was helping them program and was paid as a shift operator, feeding card decks into the mainframe and running the tape drives,” he recalled.

“But I also got to see how fast that technology was developing and how fast small changes would just open up the window for a whole new analysis.”

Despite Demers’ interest in both law and social theory, the need to pay off student loans ended up bringing him back to IBM after graduation.

“The thing that people were shocked at was that I didn’t want to go be a lawyer. I thought that law was a great education – and I still think it’s a fabulous education for anybody that wants to get into business,” he said. “But I had no real interest in going the articling route.”

Ultimately, he led a business without being called to the bar. Over the years he cultivated a hands-off, casual leadership style he said is based on letting the scientists and engineers do what they do best.

“Some sort of dictatorial directive style is not going to work. Technology is generally very smart, self-motivated, creative people, and they just need an environment where they can be successful,” Demers said. “That’s why I’m so allergic to giving interviews like this. I don’t think I’ve done one in 20 years because I don’t think it’s my job to get out there and say, ‘I’m the leader.’”

For someone who resisted talking about his background for two decades, Demers is remarkably easygoing when asked about his life and his career. But one thread he keeps returning to is how important it is for him to make his team feel empowered.

“When you look at the history of Westport, we’ve had several ups and downs. Now ironically, the downs are probably the most interesting times because that’s when we’re free to kind of do things outside the [box],” he said.

“That challenge of saying, ‘OK. Here’s a new idea. Now what do we do with this?’ was really empowering.”

@reporton