Doug Allen repeatedly uses the word “complicated” to describe work he found interesting during his long career in government.

So he may have landed in the right place as interim CEO of TransLink, a post he adopted on the eve of a contentious transit funding plebiscite. He will hold the job for the next six months.

“TransLink is a very interesting organization,” said Allen during an interview at the organization’s head office in New Westminster. “I just hope that by the time six months is up, we’re not only a better organization but people understand how well TransLink has performed in the past.”

Allen, 66, has been involved with or in charge of several big changes to the way government entities operate. In the early 1990s, he was deputy minister of health during the regionalization of the system; in 2002, he was appointed interim president of BC Ferries as it restructured to a semi-private model.

As a management consultant, he moved both the BC Safety Authority and the Land Title and Survey Authority out of government to become private authorities.

For the past three years, he’s been CEO of InTransit BC, the private corporation that runs the Canada Line and has a contract to sell its services to TransLink.

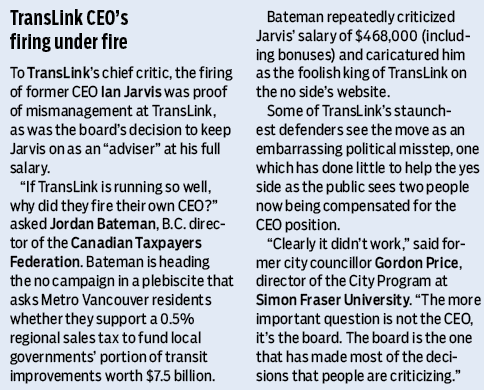

Allen’s appointment follows TransLink’s board’s decision to oust its previous CEO, Ian Jarvis, in February.

Allen, who emphasized that he commutes to work every day by bus and SkyTrain, said his focus will be on running TransLink, “finding efficiencies” and making sure major projects are on task.

Those major projects include carrying out 20 recommendations to upgrade and improve SkyTrain following two system failures last summer. Those upgrades will cost $71 million.

The long-delayed Compass Card and fare gate system is also top of mind, Allen said.

“I’ve been spending a lot of time getting briefed on exactly where it stands, what the issues are and how we can be successful at every stage of rollout of that program,” he said.

He also plans to turn his attention to customer service and to improving communication between TransLink, the media and the public.

Allen said he will draw on his experience with the Canada Line to emphasize seemingly simple things, like smoothly running escalators and elevators and improved signage.

“There isn’t any substitute for speaking to customers about not only how we’re doing but things we’re proposing to change or things they think we should be changing,” he said. “There’s a customer interface here that needs special attention.”

Although he has a wealth of experience transforming public entities into private or semi-private ones, Allen’s mandate at TransLink does not include exploring privatization. But he said he believes private or hybrid entities are often more accountable.

“Every one of these entities that are purely private or a hybrid, the focus is on performance measurement, and that has tremendous pluses in my mind,” Allen said.

Finally, Allen will also be responsible, with the board, for finding a new CEO.

That’s where it gets tricky, said Gordon Price, a former Vancouver city councillor and director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University, because of the competing political interests at play.

For years, TransLink has been pulled between the province and the region’s mayors, a relationship that was not improved when, in 2008, then-transportation minister Kevin Falcon took governance of TransLink away from a regional Mayors’ Council and handed it to an appointed board.

In 2013, Transportation Minister Todd Stone handed over responsibilities for regional transportation strategies and setting executive pay; the board still has responsibility for operations.

“I think it’s way too early to say what a CEO should be doing if you don’t know the intent of the province [or] the outcome of the referendum,” Price said. “And you don’t know what the mayors would push for.

“So you’ve got maybe three distinct sets of marching orders – why would any CEO take that on?”

Ideally, the CEO should be an “unabashed champion of transit,” said Brent Toderian, Vancouver’s former chief planner and a vocal supporter of the yes side. They should also not be afraid to speak up when they think the wrong decision is being made.

“At the end of the day, if the elected officials do the wrong thing, it’s their prerogative to do the wrong thing, and it’s the civil servants’ job to implement the wrong thing as best as they can,” Toderian said. “But up to the point of that decision it’s their job to speak out.”

Toderian and Price have both criticized the provincial government for its habit of readily funding road and bridge improvements while transit funding stalls. Toderian was skeptical that a chief executive matching his idea of an effective CEO would be hired.

“Many organizations say they want that kind of leader, but in truth they don’t really, because they think it’s easier to have someone they can control,” he said. “I’m sure Ian Jarvis was doing exactly what they wanted him to do. But in the end he was also the easy guy to cut.”

As to who the next CEO will be, Allen is sure of only one thing.

“I am not a candidate.”

@jenstden